For publicly traded companies, it has long been established that buyers often overvalue the synergies to be had from acquisitions. It is known as the “winner’s curse” – the majority of shareholder value created in an acquisition is likely to go to the seller and not the buyer. Similar research on privately-held firms, the large majority of which are family-owned, is relatively scarce.

Academics have put forward many theories to explain why few M&A transactions produce the desired, or expected, benefits for acquiring firms. Buyers usually face an acute lack of information – they have little data on the target company, limited access to executives or other stakeholders, and they often have insufficient evaluation experience. Even seasoned buyers and their investment bankers mostly focus on financial due diligence at the expense of strategy, people, corporate culture, and company structure due diligence. Furthermore, post-merger integration planning rarely gets the needed priority or visibility until after the deal has closed.

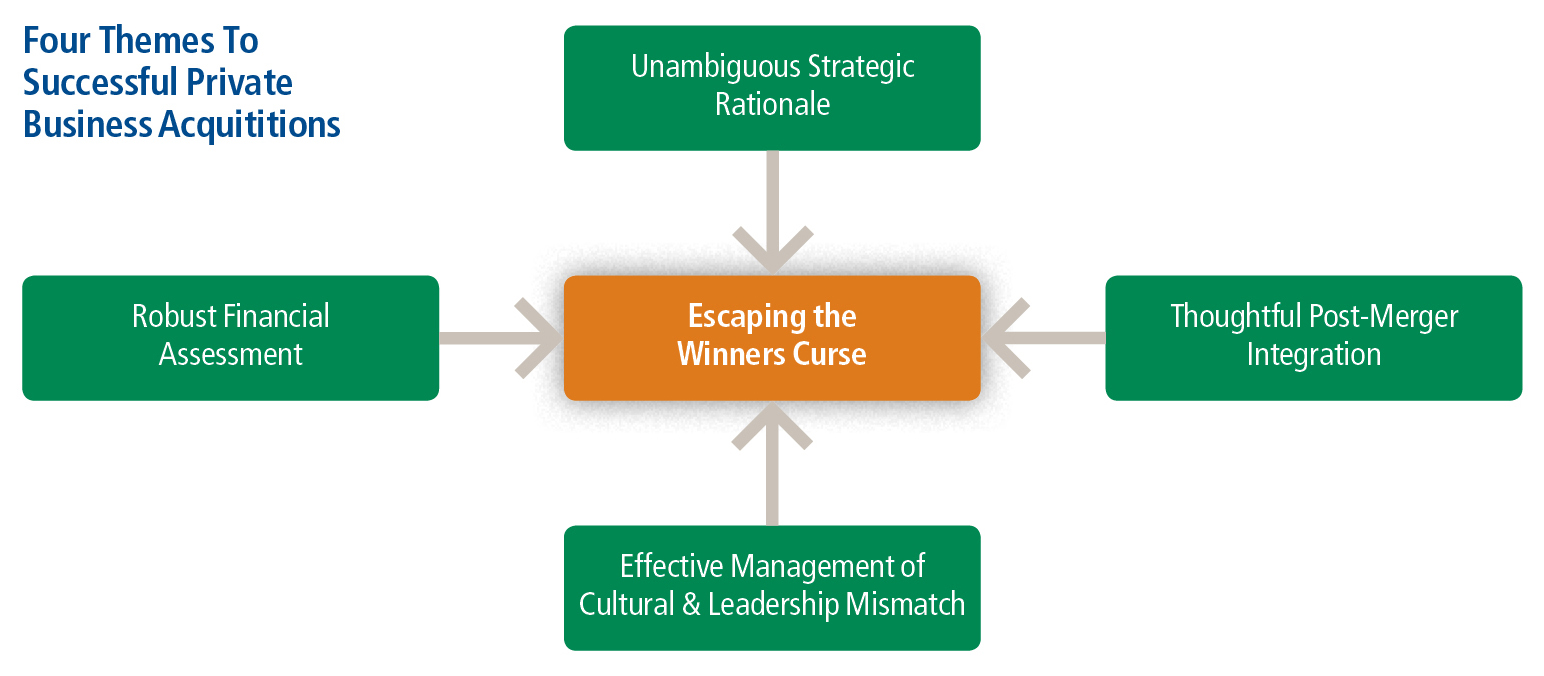

Do these concerns apply to privately-held business M&A as well? Yes, although we think some reasons might be different. Combing through our years of experience, we have come up with some practical advice to enhance acquisition success.

We published a series of IN$IGHT articles on “Improving Acquisition Success” in 2016. In those articles, we focused on financial assessment of the target and explained how many failed acquisitions are due to misjudgments on sustainability, capabilities and price.

In this new series, we will focus on three other factors that drive acquisition success: clear strategic rationale, thoughtful post-merger integration, and the effective management of cultural and leadership mismatch.

Part I – Clear Strategic Rationale

Successful acquirers have well-developed value creation ideas that drive their interest in an acquisition. Less successful acquisitions are often accompanied by ambiguous rationales, such as supporting growth, providing access to new skills, or adding sophistication to the business.

In our experience, private business acquisitions that create value almost always fit into one of these five well-defined categories: running the target more efficiently and profitably, gaining customers, eliminating competition, cheaply acquiring transformative skills or technologies, or improving scale in specific business areas.

1. Running the Target More Efficiently and Profitably

Many private businesses can benefit from a more professional management to improve their stand-alone performance. Many operate based on rules of thumb and instinct. Often performance can be improved by measuring activity in a granular way, establishing repeatable processes, and upgrading the talent pool in certain functional areas.

All of this requires active management because the assumption is that the existing team doesn’t already do this and change will need to be embedded within the culture.

2. Gaining Customers

A common impetus for M&A is to gain access to new customers and cross-sell to existing customers.

Smaller private businesses often struggle with sales – it is hard to get access to and then nurture prospects with a stretched-thin sales force, covering limited locations. An acquirer with a larger, more-sophisticated sales force can often quickly overcome these limitations and thus accelerate the target’s revenue growth. Years ago, our client, Nile Spice Foods, was acquired by Quaker Oats. On the day the acquisition closed, Quaker’s sales force presented the new product line to all of their North American grocery customers. Sales boomed almost instantaneously.

Success with this strategy requires the target’s products to be closely related to those of the acquirer. In our experience, unrelated diversification rarely works.

3. Eliminating Competition

Mature industries, often in capital-intensive sectors, tend to develop excess capacity over time. The strategic rationale for M&A in these situations is “eat or be eaten.”

After consummating the deal, the acquirer quickly closes less competitive facilities, reduces the size of the workforce, and rationalizes operations. Furthermore, exchanging fixed costs for variable costs can bring significant gains. Execution speed determines whether this strategy succeeds or fails.

An example of this occurred in the Alaskan Seafood industry when Glacier Fish bought Alaska Ocean. Both companies operated at-sea catcher processors. Both were profitable but operated far below capacity. Following the merger, one vessel was quickly “parked” and all combined fishing operations were loaded on a single vessel. This was an example of where “1 + 1 = 4”.

In some cases, weak competitors – usually with low pricing – harm everyone in the industry. However, consolidation by one party can help all remaining competitors too, the classic “free rider problem”.

4. Cheaply Acquiring Transformative Skills or Technologies

This approach works best in industries with ever-shortening product life cycles. In these situations, acquisitions can be a cheaper substitute for in-house research and development.

Acquirers might get access to technology more quickly than building it themselves. In industries where “patent thickets” are common, acquirers can save on royalty payments and potentially keep key technologies out of the hands of the competition.

To succeed with this strategy, acquirers need solid evaluation processes to truly understand what they are buying. Acquirers also need world-class integration talent. Second-rate technology and poor integration cannot lead to first-rate performance.

5. Improving Scale in Specific Business Areas

Acquisitions often aim to grow scale. However, generic economies of scale rarely justify the acquisition price.

Success requires gaining scale in specific parts of the business that will truly help the acquirer or the target become more competitive. For instance, economies of scale around purchasing might be key if industry profits are driven by materials cost or if suppliers yield a lot of power.

This strategy only works if either the acquirer or the target is not already operating at scale. Each industry also has its own optimum scale, and growing any larger can actually be a disadvantage because of the so called “diseconomies of scale”.

Avoid the Siren’s Song

Sometimes imagination exceeds operational ability, leaving the acquirer saddened by failure to reach lofty goals. We caution acquirers justifying a transaction based on 1) being cheap, 2) achieving scale benefits in a “rollup”, or 3) valuing a target based on lofty and unproven future results.

Finding something “cheap” is the opposite side of looking for a low-flying pigeon. The truth is that they rarely exist in the wild. There is usually some reason for being cheap and the buyer is usually disadvantaged in determining what that is.

Rollups rely on talent, processes, and scale that none of the rollup parties have beforehand. Combining a number of low value businesses to create a much more valuable business is a tough road. It is not that some rollups haven’t been successful, but far more have not.

Excel is a magical tool. Combined with an imagination of “what could be”, the user can prepare a future that is attractive. This is where only venture capitalists can make money. Their experience is different than that of most traditional business investors and operating company managers.

On to Integration

With most M&A transactions, the focus is usually on preparing and executing the deal. However, once a transaction is complete, it is still quite a challenge to merge the two entities. In the following articles in this series, we will share our thoughts on post-merger integration and how to manage cultural and leadership differences.