Our clients are generally entrepreneurs or families who have built successful businesses over many years or decades. When they finally reach the difficult decision to sell, most do not contemplate retaining a piece of the business after a transaction. This is not because they have a negative view of the business, but instead have poured so much of their lives into their businesses that to retain any involvement – financially, operationally, or emotionally – conflicts with their decision to sell.

For many prospective buyers – strategic parties in particular – a 100% sale presents no problems. Most private equity (“PE”) buyers, however, strongly prefer selling shareholders retain a piece of ownership in what is colloquially known as an “equity rollover.” What an equity rollover means to the seller in terms of economics, risk, and eventual liquidity for this retained investment are important to understand before seriously considering.

What is a Rollover and Why is it Important to PE Firms?

Equity rollovers are a reinvestment by sellers into the newly-capitalized company. In other words, they sell less than 100% of their interest with the balance being equity in the new capital structure. Equity rollovers generally result in post-transaction ownership by the seller in the range of 10 to 40%. In a 30% rollover, for example, the private equity firm would own 70% of the newly-capitalized equity in the business, with the seller “rolling” a portion of sale proceeds into 30% of the new equity. One primary benefit to sellers is that rollovers are generally done on a tax-deferred basis.

For a variety of reasons, most private equity firms strongly prefer equity rollovers. The primary reason is the asymmetric information advantage a seller has over a buyer. In other words, “this owner has operated in his/her industry for 30 years, why sell now?” Sellers who accept an equity rollover signal confidence to private equity buyers that continuity will be assured and the interests of the seller and buyer become aligned. Additionally, a seller’s “skin in the game” provides investors with some comfort that those who built the business are incentivized to help if fortunes change, since they retain an economic interest in the business. Lastly, in some cases, the rollover is advantageous because less capital is required to be invested by the buyer.

Mechanics of a Typical Rollover

Owners contemplating an equity rollover often find themselves facing a new world in terms of capital sources and leverage. Most of our clients have simple and relatively unleveraged capital structures, generally consisting of a single class of stock (perhaps split among a very limited number of shareholders, but often just the founder) and a modest amount of bank debt. Private equity capital structures typically consist of multiple tranches of debt (or one large piece of “unitranche” debt) and can include differing levels of preference in the equity structure. The increased complexity and leverage are not business characteristics many owners are experienced or comfortable with.

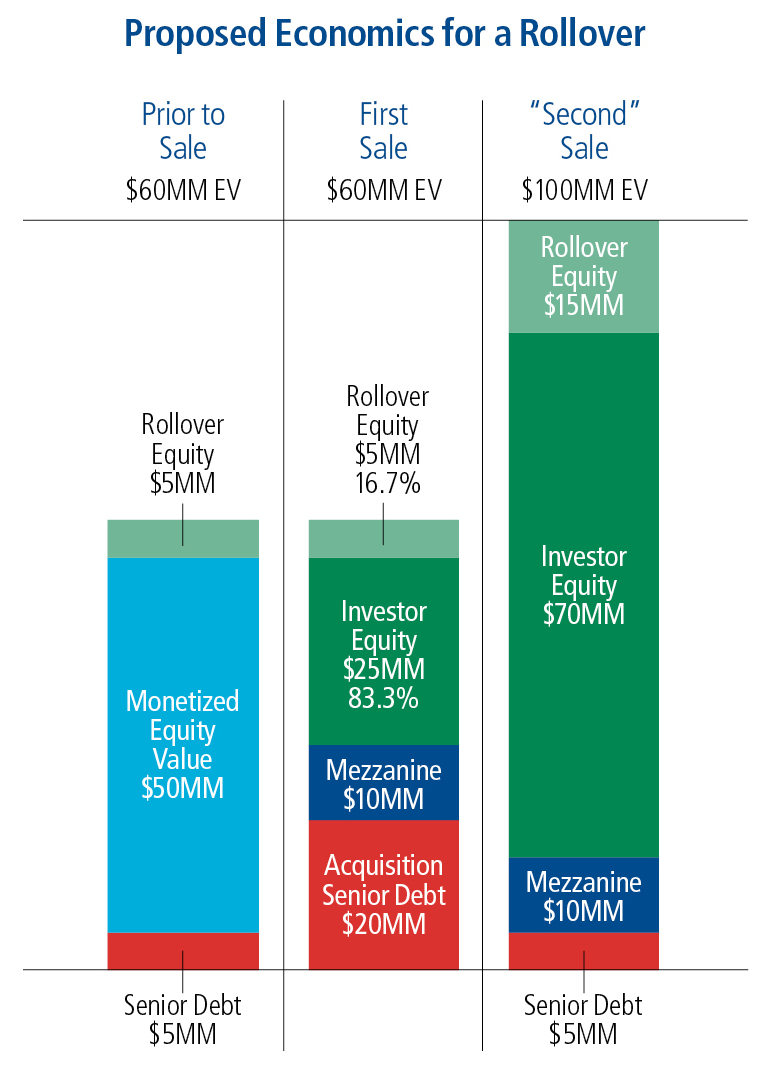

Consider the hypothetical transaction involving an equity rollover illustrated in the graphic below. Two brothers jointly own a distribution business where they are considering a transaction with a private equity firm. The headline enterprise value is $60 million, the outstanding debt is $5 million, and a $5 million equity rollover has been requested. After paying off the debt and reinvesting the $5 million, the brothers pocket $50 million. The new capital structure in the middle column is 50% equity and 50% debt (a mixture of senior and mezzanine debt), with the PE firm owning 83.3% and the brothers owning 16.7% of the recapitalized equity.

Leverage is implicitly touted as a benefit to sellers considering a rollover as PE firms explain the “second bite at the apple.” In this case, the business grows, debt is paid down, and the business is eventually sold to a strategic buyer paying $100 million for 100% of the business. The third column illustrates the ultimate outcome, with the brothers parlaying their $5 million equity into nearly $17 million.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Equity rollovers offer substantial upside, substantial downside, and pose lots of questions. Because the rollover structure is likely something an owner has never encountered, they should keep asking questions until they’ve satisfied themselves of the answers and that the transaction outlined is acceptable. Unfortunately, many owners don’t know where to begin the questioning.

PE investors generally operate with a more leveraged capital structure than family-owned firms. While added leverage boosts equity returns, risk increases as well. For the PE firm considering this business as one in a portfolio, the risk/return ratio might be more suitable than for the seller with this being their only investment. PE firms love to promote success stories, particularly the instances where an owner made more on the second bite than in the initial sale. A seller doesn’t typically hear about the disasters, the probability of which increases with greater leverage. A seller considering a rollover should ask for a pro-forma capital structure, as well as the detailed financial projections the PE firm has created to support such a capital structure, and evaluate its risk within the context of familiarity with the business and its cycles.

Further, owners rolling equity need to fully appreciate that while they are partnering with the PE group “buying” their company, the seller’s influence over important decisions may be minimal. Compatibility with regard to strategy, expectations, and performance under stress are important to assess before becoming partners. People matter. Some firms assign junior members to a new portfolio company to monitor the business – usually by burying management with requests for information and data they have never previously used in the business. Others rely on a board of directors, sometimes populated with experienced business leaders. It is important to become comfortable with the style as well as the decision-making rules of the governance agreement.

Some firms expect a hidden form of return that often doesn’t show up until the deal is being documented. Fees for management and putting the deal together, or preferred returns all contribute to a skewing of the returns among the parties. PE firms will argue these expenses are non-recurring and therefore shouldn’t affect value in a future sale, but they are real cash expenses that alter the return profile of the two parties. Asking for a complete schedule of proposed fees earlier in the process will reduce unpleasant surprises further down the road.

Equity rollovers present real opportunities to owners that want to take some chips off the table while still preserving an ability to share future upside in the company they have created. For those considering a rollover, be sure to at a minimum ask about the following:

- Taxes – confirm that the transaction enables a tax-deferred rollover;

- Corporate governance – what say does the seller have in ongoing strategic, operating, and financial decisions?

- References – how has the PE group behaved as a partner to previous sellers?

- Debt – make sure there is no personal guarantee of the debt in what will most likely be a more leveraged business.

Those seeking a clean break, both financially and emotionally, might find themselves disappointed if the primary market for their business is with financial investors. Getting some advice in advance of engaging discussions with investors as to what should be expected and how to maximize the result is wise.