In the previous issue of IN$IGHT, we discussed why successful private business acquisitions need clear strategic rationale. In this article, we explain why post-merger integration (“PMI”) is important and share some learnings from our work with successful acquirers.

Fundamental to all M&A deals is the continuation of the business trajectory and the promise of capturing synergies. While a continuation of the existing business is often taken for granted, the effort involved in the deal process can distract management from this central goal. Synergies can increase revenues, reduce costs, or accomplish both. Effective PMI is critical to assurance of a steady base and realizing these synergies.

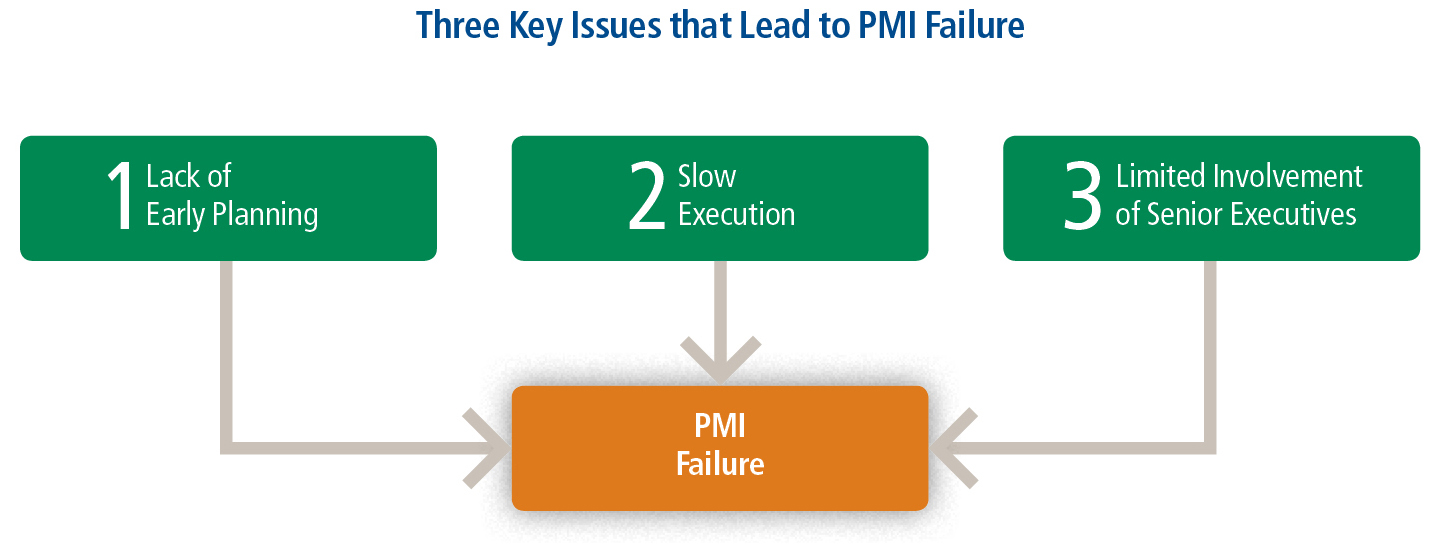

While each PMI effort is unique, they are all challenging, time consuming, and demand extensive planning. Executives consistently underestimate the capabilities and resources required to successfully integrate acquired businesses. In our experience, most PMI failures can be traced to three key issues: lack of early planning, slow execution, and limited involvement of senior executives.

Start PMI Planning Early

Many M&A teams emphasize risk and financial due diligence over development of post-closing action plans. In order for the target business to perform after the acquisition, people actually have to do things and, to achieve synergies, they have to do something different than what they did before. Even in the face of acute lack of information about the target and limited access to key employees, converting the beauty of the spreadsheet into concrete actions and responsibilities is essential.

To improve the chances of capturing synergies, we have seen successful acquirers expand the due diligence team to include individuals with a deep understanding of both the target’s and the acquirer’s customers, products, suppliers, distributors, or functional units. The choice of these individuals should reflect the deal’s strategic rationale. For example, if an important objective of the transaction is cross-selling to existing customers, the due diligence team should include individuals with a deep sales and marketing background.

While it is important to start PMI planning with the right resources early, it is equally important to temper short-term enthusiasm. There is often a temptation to overstate synergies or to be excessively enthusiastic about how quickly they can be realized. However, PMI planning should be realistic and, ideally, the individuals tasked with functional due diligence should also be accountable for delivering PMI outcomes.

A meaningful end product of the planning effort would be a well-defined “integration playbook” that catalogs key synergies and the critical tasks to be performed during integration, along with responsibilities, timelines, and inclusion into management incentive plans.

We witnessed the impact of well-developed integration plans in a recent M&A transaction in the trucking industry. Well before closing, the acquirer created clear plans for route and terminal consolidation, driver integration, and customer communication. As a result, the acquirer captured most of the expected synergies far ahead of schedule.

Accelerate Execution

Integration delay often erodes business value. Following the trauma of the transaction, it is not unusual to have buyer executives put a moratorium on change to stabilize the organization. It is also not unusual to hear the statement, “we are going to take the best from each organization and create an even better organization going forward.” In either case, value capture of synergies is delayed and the opportunity to affect change is made more difficult as the entire organization is confused as to the direction and course.

There are two kinds of integration – business administration and business model alignment. The former deals with issues such as consistency of pay scales, reporting structures, benefit program conversions, policies and procedures communications, and systems. The latter deals with the ways in which the combined business reacts with its supplier and customer base in order to maximize its position in the market. Examples might be consolidation of sales force and coverage realignment, eliminating redundant functions and people, or consolidating facilities and processes. After the transaction closes, many acquirers set up an integration team to manage the transition, with primary emphasis on integrating business administration functions, with the real value creating actions taking a backseat.

Some acquirers expect people to integrate themselves. This is wishful thinking. The truth is that businesses don’t merge, at least effectively. Resolution of people and power issues should not be delayed. Successful combinations are almost always a takeover with one culture, mission, and strategy surviving. Converting the acquired into that overall strategy is the most important integration function that can be accomplished. Delaying achievement of that goal can confuse the employee base and its customers. Business performance suffers, and competitors are all too happy to take advantage of the situation.

Our experience executing transactions in the U.S. waste and recycling industry leaves us impressed by the industry’s rapid pace of integration. Executives did not shy away from making tough decisions and integration teams ensured everyone stuck to the playbook timetable. In contrast, we have also been part of mergers in the seafood industry where acquirers took years to consolidate plants that literally sat next to each other never achieving available operational and cost efficiencies.

Involve the Executive Leadership

Executives need to be actively involved in managing the integration, setting the pace, making tough decisions, monitoring performance, and celebrating integration victories. Leaders should specify which integration issues are non-negotiable as early as possible. For example, it might be prudent to specify migration to a unified IT platform instead of debating whether the target should be allowed to keep its data systems. Closing facilities, laying off people in redundant functions, and reassigning accounts and sales coverage should be done with urgency. Change needs to occur as quickly as possible so that the future can become the important focus.

In our experience, successful leaders embrace “selling” the deal to employees. They need to proactively and meaningfully address what the deal will mean for the future of all employees, not just customers or shareholders. The leadership team should quickly commit to the culture they want the integrated entity to embrace, with personnel and compensation decisions rewarding individuals that embrace the new culture, not resist it.

Is This Enough?

The PMI suggestions discussed above work best when the target operates in the same industry or faces the same competitive threats as the acquirer. These efforts also work in situations where the target is kept operationally separate from the acquirer’s core business or where the objective of the acquisition is simply to acquire certain skills and technologies.

On the other hand, some M&A transactions are unrealistically ambitious. Simultaneously entering new markets, incorporating new channels, introducing new products, and/or fully merging operations complicate the already difficult PMI process. Obviously, such transactions have exponentially higher PMI risks and correspondingly high rates of execution failure. Leaders are advised to proceed at their own risk or go back to the drawing board to (re)define the strategic rationale.

On to Culture

As we have seen, capturing sustained economic value in any M&A transaction can be challenging. However, regardless of deal size or complexity, managing “the way we do things around here” – also known as culture – is a key determinant of long-term success. Our final article of this series will discuss how to analyze, define, and bridge cultural differences.