Private businesses are notoriously hard to value. Because no liquid market for ownership exists, M&A practitioners typically rely on derivative methods to ascribe value to a private business. Each method has its own shortcomings, which can collectively suggest a view on business value that is not representative of the outcome of a competitive sale process. A deeper understanding of the philosophies and flaws of traditional valuation techniques can greatly assist owners to form a thoughtful view of their companies’ value, as well as improve their ability to communicate that to the market.

Since there is no definitive source to estimate the fair market value of a business, no “right” answer exists. The typical valuation assessment is conducted according to three methods – discounted cash flow analysis, comparable public companies, and comparable transactions. Widely different conclusions among the various methods are not uncommon, with the final assessment simply weighting the different methods – averaging to find “truth.”

We estimate the market value for virtually every one of our clients, and then, as a result of a market process with actual buyers, find out how accurate we were in our estimate. We are painfully aware of how difficult this exercise is. This experience has provided us with a perspective on how the different valuation methods can be utilized best to make decisions. The two following principles help us give advice to our clients:

- The value of a business is based on future expectations, not what it has done in the past. The past certainly helps shape views on the future, but one shouldn’t underestimate the psychology of the buyer, and how that affects their views of the future – either optimistically or pessimistically.

- There is not one value for a business, with real economic reasons creating significant differences among buyers.

We first establish a standalone value of the business based on its current market position and strategy. Then we determine how and why someone else might be able to pursue a different future course, as well as the resulting implications on value. As an example, a business valued at $50 million on a standalone basis could be worth $75 million in combination with another business. Averaging the two values to get $62.5 million is wrong in both regards. This is why valuation approaches should be chosen that best allow the appropriate question to be answered.

DCF Model

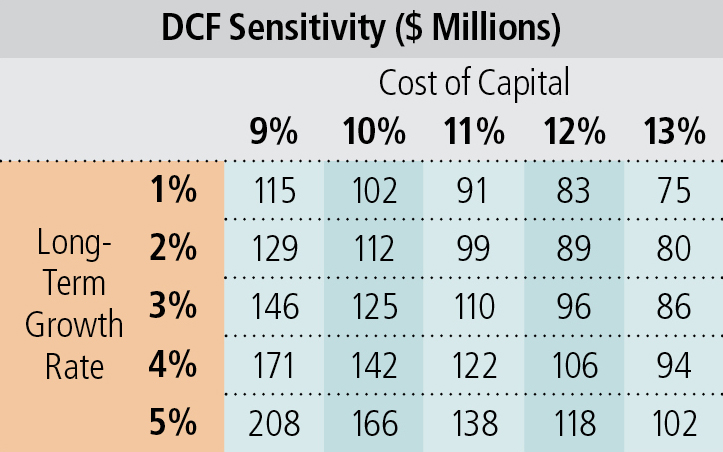

The most well-known valuation technique is the discounted cash flow (DCF) model.  A great analytical tool for evaluating future scenarios, the perceived utility of a DCF is based on the theory that businesses are valued on the cash they will generate in the future. DCF-based valuations are alluring because of their purported precision, as an elaborate model with growth, margin, and capital investment assumptions produces a singular value. However, as with any model, the output is only as good as the inputs. In particular, DCF models are particularly sensitive to assumptions regarding the “terminal period,” which is often just three to five years from today. In some cases, this terminal value calculation could make up 75-80% of the value. As seen in the exhibit below, slight alterations in long-term growth or discount rates have massive implications for value. For our hypothetical company, a few minor tweaks of the terminal growth and cost of capital yields value conclusions of anywhere from $75 million to $208 million.

A great analytical tool for evaluating future scenarios, the perceived utility of a DCF is based on the theory that businesses are valued on the cash they will generate in the future. DCF-based valuations are alluring because of their purported precision, as an elaborate model with growth, margin, and capital investment assumptions produces a singular value. However, as with any model, the output is only as good as the inputs. In particular, DCF models are particularly sensitive to assumptions regarding the “terminal period,” which is often just three to five years from today. In some cases, this terminal value calculation could make up 75-80% of the value. As seen in the exhibit below, slight alterations in long-term growth or discount rates have massive implications for value. For our hypothetical company, a few minor tweaks of the terminal growth and cost of capital yields value conclusions of anywhere from $75 million to $208 million.

As challenging as it is to predict the future, knowledgeable operators often have strong instincts as to what is actually achievable. Supplementing those instincts with strategic market analyses and the company’s competitive position can provide a rational set of assumptions about the future and an evaluation of the sensitivities of the output to key drivers helps to establish the baseline for an individual company.

Comparable Public Companies

A second common approach is to investigate how comparable public companies are valued. A primary flaw in this approach is that there are typically very few (and often no) comparable companies to the one being evaluated. Analysts use industry classifications to identify comparable companies because companies in the same industry tend to share similar economic characteristics. However, as noted by Lee, Ma, and Wang[1], industry classifications are at best crude guidelines for identifying comparable companies: “With no conceptual guidance on what constitutes an ‘industry,’ the choice of industry benchmarks ultimately relies on subjective judgment.” Many of our clients earn superior returns on capital because they operate in niche markets where truly comparable companies simply don’t exist. Further, most public businesses are much larger, more complex, and hold different market positions than privately held businesses, making relevant comparison difficult. Simply averaging the results and assuming these differences will give precision in application to a privately-held business is a specious conclusion.

Comparable Historical M&A Transactions

The final commonly accepted method to determine business value involves analyzing “comparable” historical M&A transactions. The perceived benefits are that, unlike a DCF, comparable transaction analyses provide a market-based perspective on the value of similar businesses. Real dollars have been invested at the stated valuations, indicating a level of relevance hard to achieve with the largely theoretical DCF. However, there are a number of significant drawbacks that warrant caution when using this method. Like comparable public company analyses, the ability to identify truly comparable transactions is vital when using multiples as a valuation technique. Further, most private transactions disclose very little financial information – typically only when required by regulatory agencies – and so deriving relevant takeaways for valuation purposes is often impossible. Lastly, as we often see in transactions, the EBITDA or revenue multiple stated was not reflective of the economics the buyer planned to assume. Extraordinary owner compensation, non-recurring expenses, operations consolidation, supplier pricing power, and various other factors can make the observed multiple irrelevant to the contemplated economics of the transaction. The multiple is simply the result of other factors, not the causal agent. Ultimately, the most valuable exercise is to determine potential strategies by different buyers and what that might mean in the specific situation being assessed.

More Art Than Science

The standard approaches utilized by investment practitioners to value privately held businesses should be viewed as a starting point rather than a conclusion. Valuation is more art than science, and as a result, seasoned investors seek myriad approaches to try and find “truth” in a sea of irrelevant data. Each approach has both merit and drawbacks that limit their usefulness in drawing specific and meaningful conclusions. Business owners should be aware of these shortcomings and take the “typical” valuation conclusions with a grain of salt. Using these conclusions to form a framework for thinking about the value of a business can be immensely helpful in providing a basis for evaluating the cost of new capital, the potential of different strategic initiatives, and proposals from prospective acquirers.

[1] Lee, Charles M.C., Paul Ma, and Charles C.Y. Wang. “Search-Based Peer Firms: Aggregating Investor Perceptions Through Internet Co-Searches.” Journal of Financial Economics 116, no. 2 (May 2015): 410–431