Expected future growth is arguably the most critical element influencing business value. How much, at what rate, and for how long a business can grow can overwhelm other variables in assessing the future profitability of a company and therefore its current value. Growth is coveted, but sometimes without enough thought given to the incremental operating expenses and capital investments necessary to achieve a higher growth trajectory. In other words, how well can the company’s support systems scale to support the forecasted growth?

In this two-part series, we’ll take a closer look at 1) what constitutes “good” growth and how to identify opportunities; and 2) tactical steps to take to execute growth initiatives.

PART I: Identifying Value-Creating Growth

The nearly unquestioned belief that “growth is good” permeates public and private markets, with rapidly-growing businesses being valued at higher multiples than slower-growing businesses. But growth is not inherently value-creating, as we’ve written about before (“Staying Smart About Growth,” Winter 2015). How do we know if growth will create value for the business?

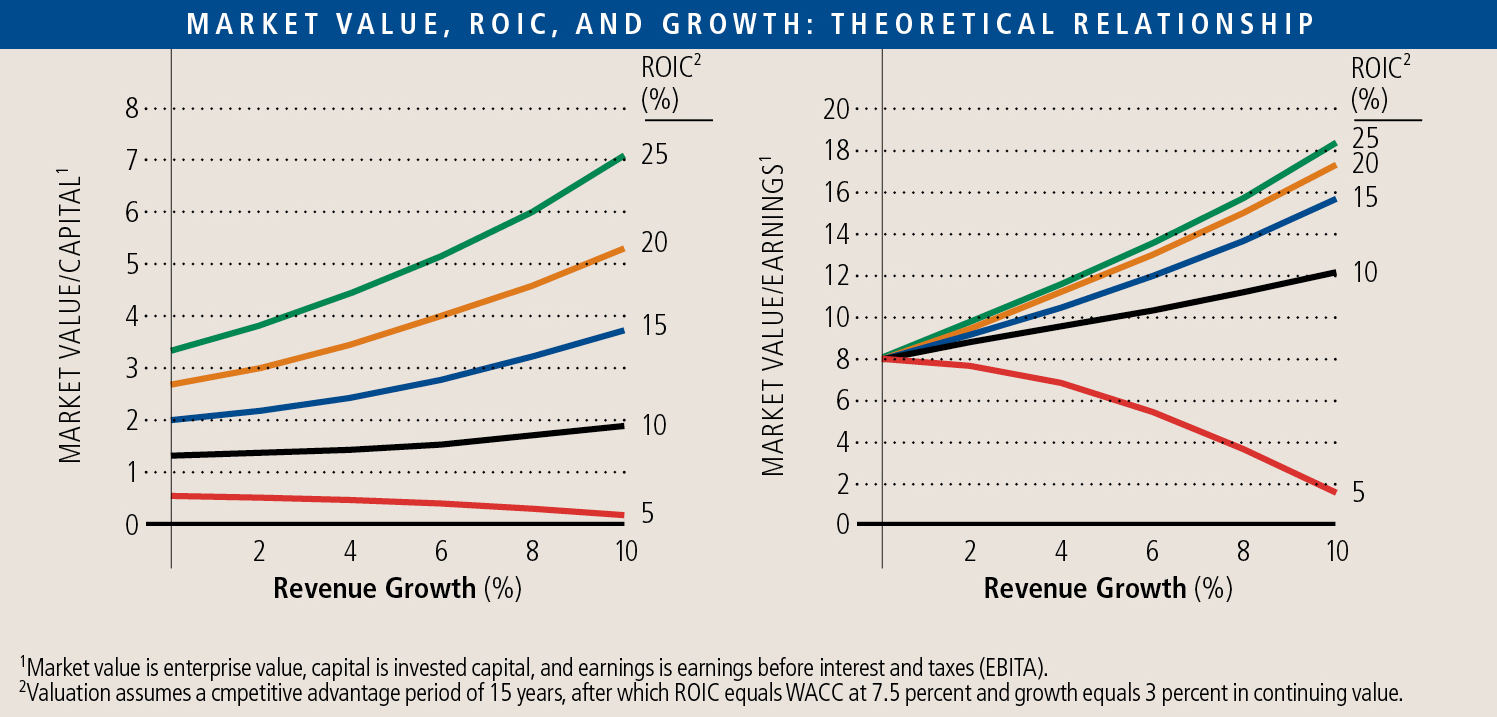

In academic terms, “good” growth generates a return on invested capital (“ROIC”) in excess of the company’s weighted-average cost of capital (“WACC”). The below chart illustrates this point, plotting five separate ROICs at varying levels of growth (assuming a 7.5% WACC). For high ROIC businesses, increasing growth rates lead to higher valuations. For the business with an ROIC below its WACC, a higher rate of growth actually yields a lower value. This is because the return on each dollar invested by the company generates a return below what its investors require to offset the riskiness of the investment. In other words, under these conditions, investors should prefer their company to eschew higher growth in favor of returning that capital back to shareholders to seek higher returns elsewhere.

This phenomenon played out for one of our favorite clients, Mikron Industries, a manufacturer and supplier of vinyl window frames. In the 1990s, new laws required homebuilders to use more efficient building materials, including windows. Prior to that, window frames were made of expensive custom wood or more affordable aluminum frames. Vinyl frames made up a very small component of the market. Once vinyl became recognized as offering a higher heat value than other window materials, its market share skyrocketed. Mikron benefitted by adding new products through its existing relationships with window companies. For several years, Mikron’s return on its growth far exceeded its WACC, creating substantial value for the family ownership. However, as vinyl windows’ market share reached their logical market position, Mikron’s growth slowed to the industry average. Before that occurred, the family chose to exit—a number of strategic buyers had aggressively pursued the company, and the transaction timing resulted in an outcome far above how the company would be valued had the sellers waited for the business to reach its steady state.

The difficulty with applying conceptual tools, like many academic applications to real-world situations, is that no one can perfectly forecast growth rates or incremental ROIC. While useful frameworks help illustrate where pursuit of growth could create value, the only concrete measure of ROIC is historical. Owners and managers must rely on assumptions about the future and assessments of opportunities to come up with the best estimates of expected return.

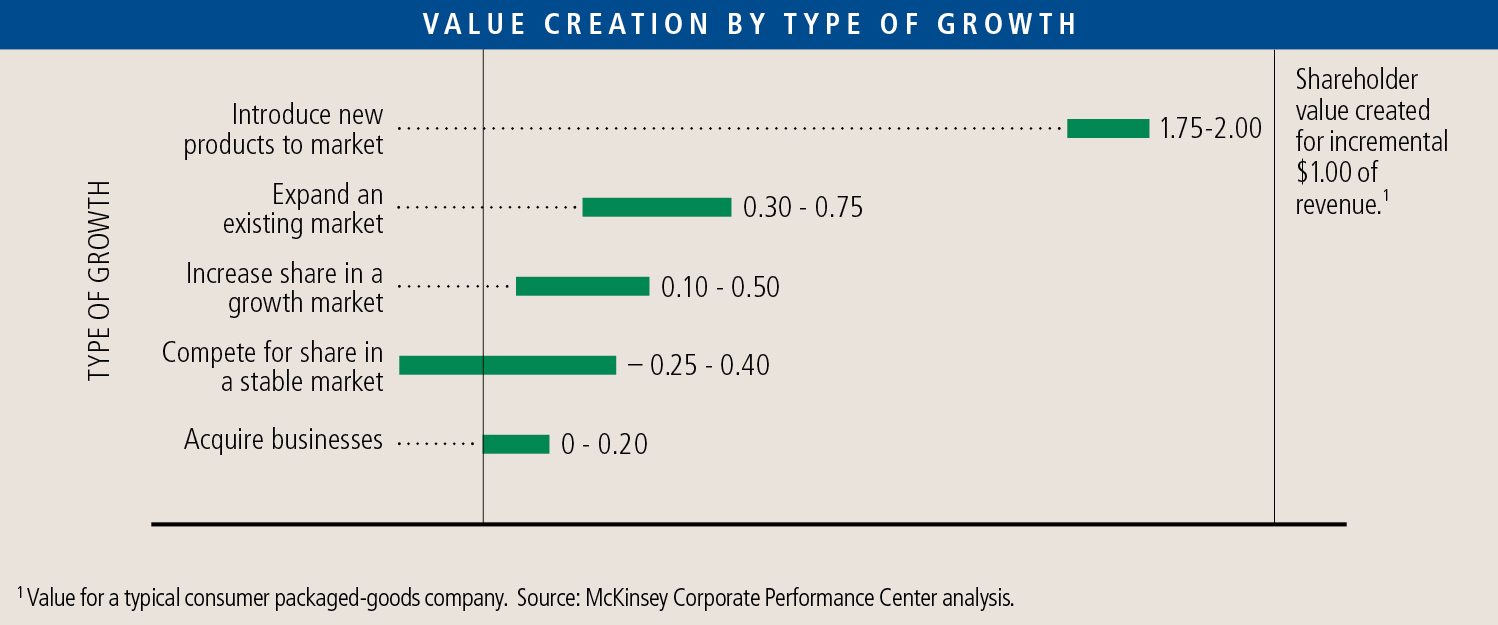

The trick is to identify growth opportunities so compelling that minor forecast errors are overwhelmed by the magnitude of the value creation. For instance, in the below chart, the researchers conclude that introducing new products or expanding an existing market (organic growth) generally produces the most bang for the buck, and are logical places to consider growth strategies. Why is that?

A helpful way to think about ROIC is “incremental value created per incremental cost.” In other words, the potential growth opportunity associated with a new product cannot be measured only as a revenue opportunity – instead, it must be measured relative to the costs necessary to fund the opportunity. It is important to note that ranking growth opportunities by value creation is unique to each situation and requires each company to consider its own situation. As an example, the above graphic shows the profile of a business where introducing a new product to a market is a relatively low-cost endeavor. The company likely has a history of introducing new products, meaning that the infrastructure to develop, market, and distribute a new product to existing customers is largely a sunk cost. The other growth opportunities featured would each require enough novel development of support infrastructure in order to support an equally-sized revenue opportunity that the ceiling on incremental ROIC for these ventures is lower. It then comes as no surprise that the other growth opportunities listed wouldn’t create as much value for this company as would the introduction of new products.

It can be difficult for an owner to recognize costly growth, because it rarely appears to be costly in the near-term and on the surface. A common example of this in our experience has been the growing consumer goods company that lands a major national or international distribution client (the Costcos, Walmarts, and the like of the world). On the surface, such opportunities appear to be a game-changing win for the company. However, after accounting for the investment to scale operations to satisfy demand and stock the channel, and with the pricing and volume terms that usually accompany the deal, it is not uncommon for the supplying company to find that its growth initiative exposed it to tremendous risk and much less value creation than was initially envisioned. This is not a broad categorization of growth opportunities with large customers, simply a cycle that we’ve seen play out enough times to establish a pattern.

Once a business owner has identified a robust strategy for productive growth, managing to execute on that opportunity creates its own set of challenges – how does one control the costs that turn “good” growth into “bad”? In part II of this series, we’ll examine common pitfalls in high-growth environments, and suggest strategies and tactics that business owners can use to mitigate those challenges.