The statistics on acquisition success, measured as realized return on investment relative to expected return on investment, are not good. Most of the research indicates that only about half of all deals are “successful.” A recent Harvard Business Review Report claims that between 70% and 90% of all corporate acquisitions are deemed failures from a value standpoint. As advisors in mergers and acquisition transactions over more than a quarter century, we have observed that the most common villains stealing success from acquisitions fall into one of three buckets: misjudgments about the duration of the business model in its industry setting (sustainability), shortages of the necessary ingredients required to perpetuate the business under new ownership (capabilities), and an over-optimistic view of future profits, capital and the relationship between the two (price).

Each business offers a value proposition to its customers, suppliers, and employees. To deliver that value proposition, the business employs capital and labor in order to produce a “profit.” Almost every business environment is dynamic, such that everything is under attack; whether from competitors, suppliers, customers, or substitutes that can challenge the validity of the value proposition that is the basis of the business. It is in this context that acquisitions are made. Not an easy job, but odds of success can be increased with thought and discipline.

Part III: Pricing the Acquisition From a Value Perspective

The two factors that affect the pricing of an acquisition are value and price. Although linked, they are different; the former is an economic judgment, while the latter is a tactic. The first two parts of this series discussed the sustainability of the business model and capabilities and competencies of the business. Conclusions drawn from those inquiries provide the basis for valuation. Pricing, on the other hand, is an outcome of a tactical decision, driven by the competitive dynamics and constrained by the value assessment. In this Part III, the impact of the strategic position of the business on valuation is discussed in the context of how much must be paid to acquire the business.

The hardest aspect of valuing any business is assessing the sustainability of financial performance. The two largest mistakes in valuing a target are optimism over the amount and timing of synergies in a business combination and the length of time the business will continue to generate abnormal (above the cost of capital) returns on tangible capital.

Valuation

Excel is a powerful yet dangerous tool for valuations. Numbers that grow “up and to the right” are easy to plug in as growth and synergy assumptions, but in reality, execution is hard, businesses have competition, and synergies are often difficult to capture.

To illustrate the effect of optimistic assumptions, consider an acquisition expected to increase combined operating cash flows by 25% in the first year and 50% thereafter. For a stable business, a lag in timing alone can harm the valuation by as much as 5-10% per year. When the amount of profits from synergies proves to be too optimistic, even more can evaporate. The relationship is linear, meaning that a 10% reduction in the amount of cash flow from synergies affects the value attributed to those benefits by the same percentage. It doesn’t take too much of a shortfall to materially affect the investment thesis.

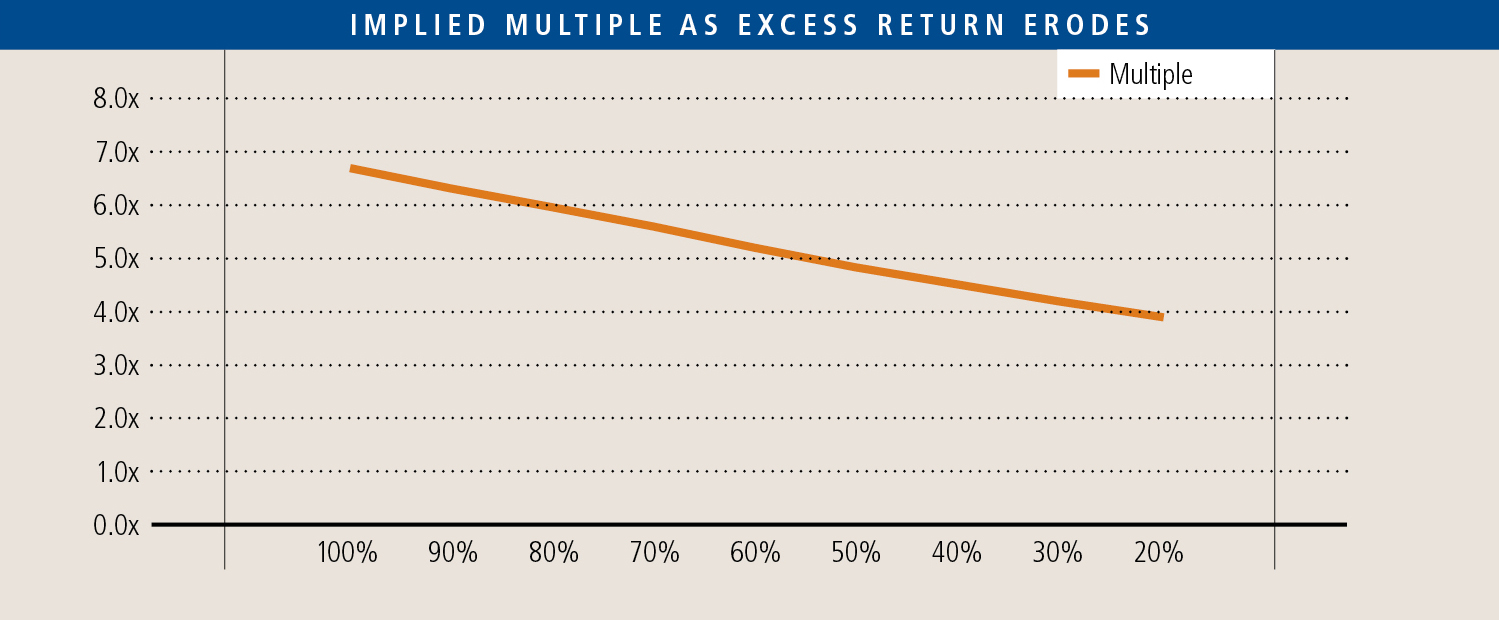

Equally or often more devastating is when an acquirer assumes economic goodwill is perpetual. As discussed in the previous two parts to the series, “excess profits” (the amount earned in excess of the business’ cost of capital) exist for specific reasons (such as unique capabilities or existing external conditions), but almost never prove as durable as management believes. With some exceptions, excess profits are often competed away over time so that all competitors earn their cost of capital. For the buyer who expected excess profits to continue, and paid for the business on that assumption, the acquisition results will undoubtedly disappoint. The graph below shows how value erodes as excess profits decline over a ten-year period. For illustration purposes, this business has $10MM of capital and earns $10MM EBITDA, or 100% return on capital. A buyer pays 6.7x EBITDA based on the assumption that the business will continue to earn that same EBITDA on the same asset base. What if that excess return is competed away over time? The chart on the previous page shows the implication of return on capital declining over a ten-year period (eg. after ten years, earning $9MM on $10MM of capital). A buyer embedding that assumption in the original valuation would have only paid 6.1x EBITDA at the purchase date.

Pricing

An acquisition price may or may not align with valuation. While the valuation establishes a framework for an acceptable deal, the price to be paid is a tactical decision based upon the nature of competition, the buyer’s desire to complete the acquisition, and the owner’s negotiating leverage.

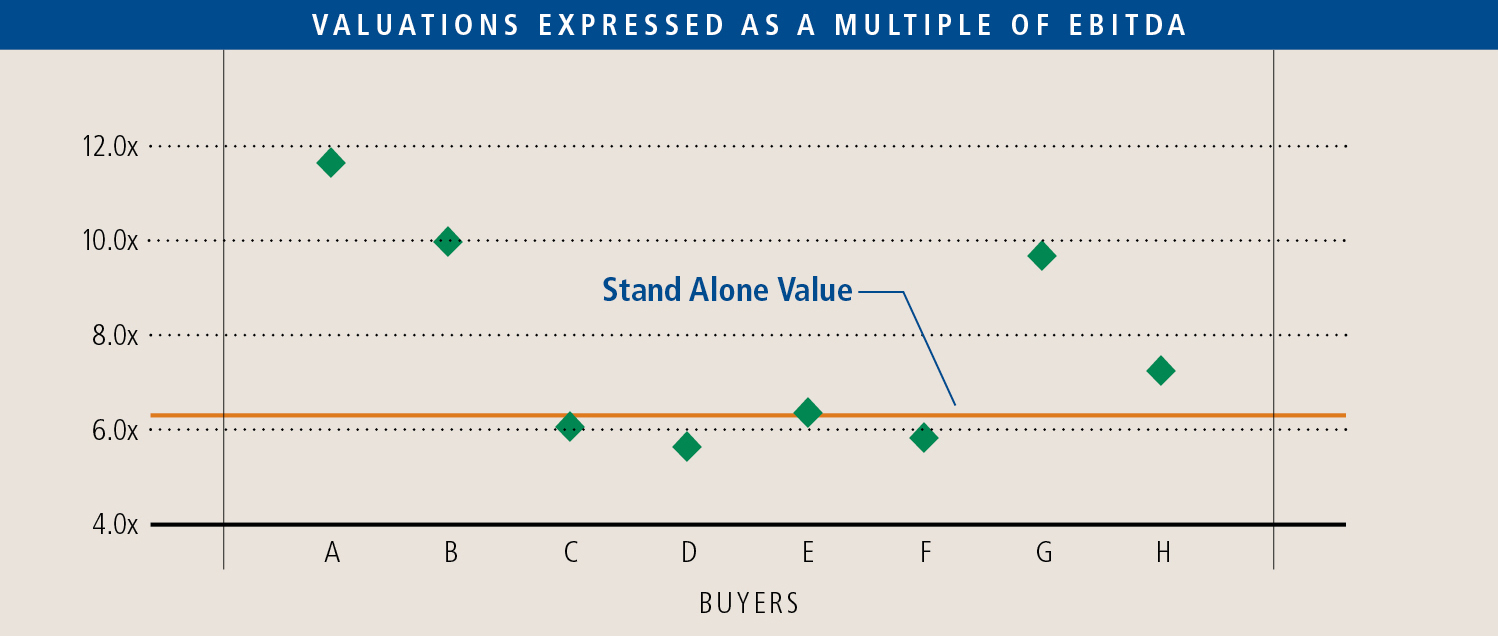

Assuming all information is available, the parties are economically rational (neither of which are always good assumptions), and no other non-economic factors are involved, the seller should value the business based on the same baseline projections as the buyer uses before considering any synergies, commonly referred to as the stand-alone value. Financial buyers usually cluster around that value, but strategic buyers can have different values unique to their particular circumstances. If the market is known, the valuation data looks like a scatter plot as shown in the below graph, with each point representing a unique value.

The only real information an acquirer has is its own valuation. Assessing the rest of the market is simply a series of educated guesses, with the strategic parties and their values being the most difficult to assess. The objective is to price the offer $1 above the next highest valuation, subject to the limit of the buyer’s own valuation.

Although the results of these analyses will never achieve 100% accuracy, the thought process can provide discipline that helps avoid wasted effort and poor investments. Not every acquisition opportunity can or should be won; there are many other buyers in the market, some of whom will legitimately be able to justify a higher value, and some who will not have the same pricing discipline. However, exercising rational analysis in the valuation process and discipline during negotiations will greatly improve the probability of a successful acquisition.