When a purchase price exceeds the amount of a target’s tangible net assets, the excess purchase price is called goodwill. Depending on transaction structure, this goodwill can be amortized as an expense to reduce taxable income, which provides incremental value to a buyer by increasing after-tax cash flow. Although buyers are acutely aware of this value, it is often not explicitly accounted for in a purchase price. Just as it is important for a seller to convey to the market the valuable elements of a company’s operations, articulating the value of this tax shield asset should not be overlooked.

Goodwill – Why Does it Matter?

In order for the buyer to gain the value of the tax shield created as a result of goodwill, the transaction must be structured as a purchase of assets (either in a true asset sale or a sale of stock or interests with both parties agreeing to a tax election to be treated as an asset sale).

When the seller entity is a pass through entity (e.g., S-corporation, limited liability company, or partnership), usually the seller is indifferent to this election. The one primary exception is that in an asset sale treated transaction, assets are required to be to be revalued at market value. If the company is an asset-heavy business and the assets have been depreciated below market value, the markup in value, referred to as a “step-up,” is taxed at ordinary income rates instead of capital gain rates. Therefore, the election will only make sense when the value of the goodwill exceeds the cost of the step-up.

In the case in which the seller’s company is a C-corporation, there is virtually no set of circumstances in which the value of the goodwill to the buyer would offset the double taxation of an asset sale and, therefore, the value of the goodwill tax shield is forfeited.

How Valuable is Goodwill to the Buyer?

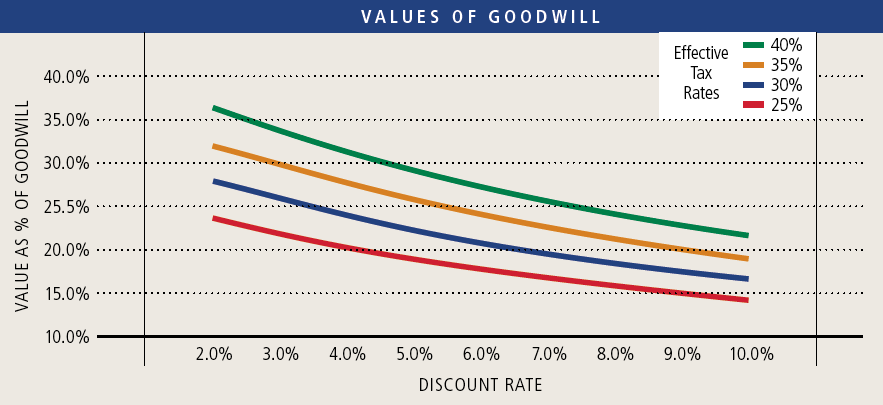

The value of goodwill to a buyer depends on a number of factors. For tax purposes, goodwill is amortized on a straight-line basis over 15 years. As a non-cash deduction against taxable income, it essentially reduces the effective tax rate and increases the amount of cash retained by the company. The primary factors affecting the value of this tax shield then are the buyer’s marginal tax rate and the likelihood of taxable income being generated during the 15-year window to which the goodwill can be applied. The value of the tax shield created is the present value of the expected tax savings, discounted by the appropriate discount rate for the projected usage.

But, that’s where it gets interesting, as not every buyer is taxed the same or has the same taxable income profile.

But, that’s where it gets interesting, as not every buyer is taxed the same or has the same taxable income profile.

Effective tax rates can vary depending on the taxable entity. Corporations aren’t taxed at the same rate as are individuals, which makes the tax shield more valuable to owners of pass through entities (S-corporations or LLCs) when the owners are tax bracket tax payers. Additionally, the employment of state level income taxes can change the equation. Forty-four states levy a state income tax, ranging from 4% in North Carolina to 12% in Iowa. When you work through the arithmetic, the value can be quite different. $50 million of goodwill to a C-corporation buyer located in a state like Washington, which has no state income tax, would be valued at approximately $15 million, while a wealthy individual gaining the goodwill through its LLC located and taxed in Iowa would value the same amount of goodwill at over $20 million.

Goodwill is less valuable when there is doubt or delay in its utilization.

The probability of generating sufficient taxable income to utilize the goodwill is much like a credit decision relative to having sufficient cash flow to cover debt service. As the margin between projected cash flow approaches the amount of debt service, interest rates climb. Likewise, as projected taxable income approaches the amount of goodwill, the discount rate also climbs. Even if the buyer projects to be able to use the tax shield, the value of it could be cut in half as the probability declines.

The following graph shows the possible range in values of goodwill depending on the likelihood of its use and the effective tax rate of the buyer.

The present value of goodwill in a transaction can vary significantly depending on a number of factors:

- Transaction type. Owners of C-corporations will likely not be able to benefit in a sale transaction from goodwill enhancing the purchase price.

- Purchase price. The price has to be in excess of the value of the tangible assets or there is no goodwill.

- Asset composition. Asset-lite businesses are likely to have the value of intangible assets be a greater proportion of the business, and therefore generate more goodwill.

- Buyer size, profitability, and type. The more taxable income there is to which the goodwill tax shield can be applied makes the goodwill more valuable. What this means is that a potentially valuable asset in the hands of one party might have little or no value to another. A very profitable corporation might value the goodwill tax shield very high while a private equity firm that applies high leverage or a corporation with large net operating losses, might put less value on the goodwill.

- Effective tax rate of the buyer. Not only the federal tax rate (corporations versus individuals), but also the existence of state income taxes, can affect the value equation for goodwill.

Conclusion

Goodwill can be a valuable asset for the buyer. Sellers should be aware of this value, but also recognize the amount of value is conditional upon many factors. Buyers should carefully consider the value of the tax asset to them in their situation, while sellers should make sure to communicate this potential value as part of a process, while also considering how different suitors may or may not value goodwill in the context of the broader transaction.