One of the many arguments in favor of using an employee stock ownership plan (“ESOP”) to facilitate an ownership transition is that ESOPs create better companies. Because employees are owners, they have a vested interest in driving greater company performance. Increases in employee productivity and accountability, and therefore company profitability and value creation, will follow.

The fact is that ESOPs would likely never occur in the wild but for the tax benefits that accrue to the selling shareholder(s), the company, and the ESOP participants. There are many alternative mechanisms to bestow gifts upon and incentivize employees, including providing equity return characteristics. These mechanisms can be customized to the situation, but generally they do not receive all the beneficial tax treatment provided to ESOPs from the federal tax code.

ESOPs have a cult-like following of advisors and advocates that make what is really a corporate finance structure almost a religious proselytization. We offer a view from a different angle.

ESOPs Don’t Buy Shares; They are Given Shares

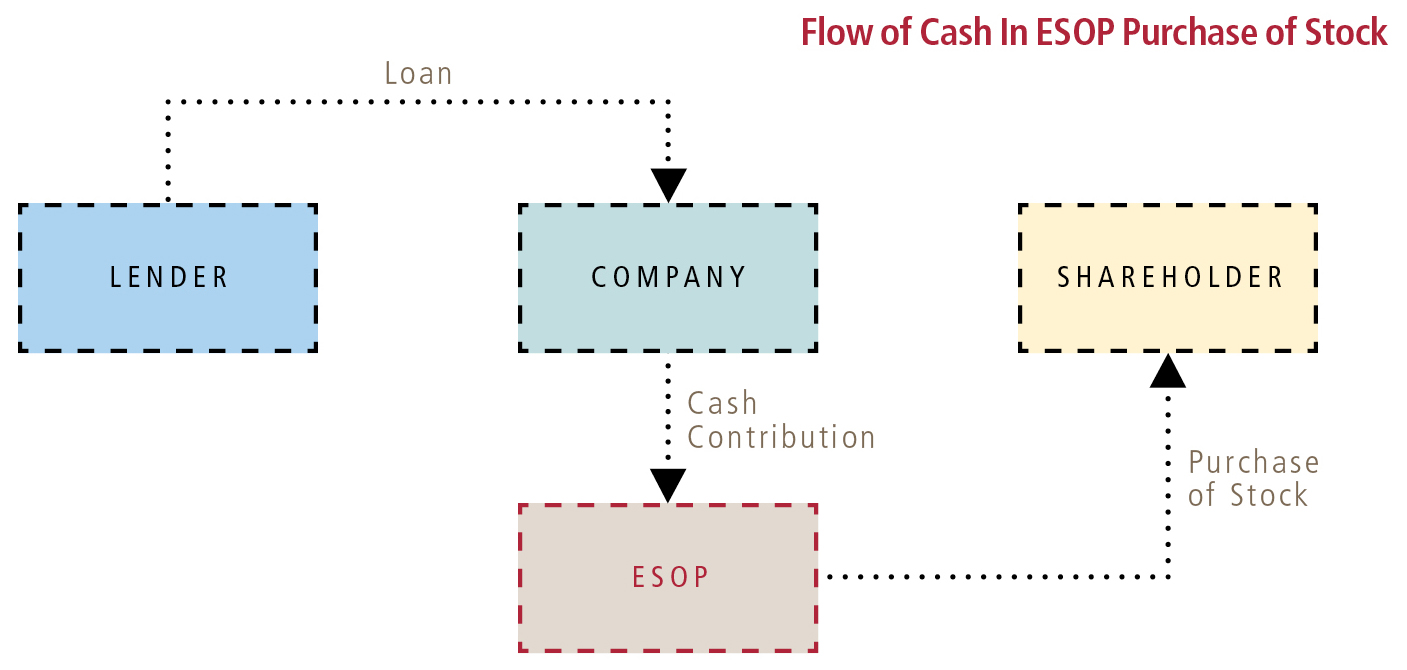

ESOPs have no capital and, therefore, no ability to “buy” anything. The structure under which an ESOP “buys” the stock of a company requires the company to “give” the funds to the ESOP to allow it to buy shares from the existing shareholders. The company obtains the funds by borrowing from a third party. The loan is secured by company assets and in some cases with seller proceeds from the sale. To illustrate the mechanics, the following diagram shows the parts of the transaction in transferring ownership to an ESOP in a company. At the end of the transaction, the owner has received cash for part of his ownership as a result of a loan to the company.

To put some numbers to it, we assume the company is valued at $30 million and a sale of 30% is made to the ESOP. After the transaction, the equity of the business has declined by $9 million to $21 million because the company now owes $9 million to its lender. Even after discounting the ESOP portion for its minority position, the selling shareholder’s 70% ownership is now worth approximately $16 million. Combined with the $9 million in proceeds from the transaction, the owner has effectively traded $30 million of value for $25 million of value.

An alternative to the ESOP transaction would be for the owner to borrow $9 million and make a distribution. In this case, the owner would have $9 million in cash and own 100% of the $21 million of company equity value.

It seems obvious that entrepreneurs don’t generally give away value so the conclusion is that owners make up the value diminution in tax benefits, benefit from growth in equity value from a far more productive work force, or obtain a sales price greater than could be achieved with another buyer.

What are the Tax Benefits?

The primary tax benefit to a seller is the ability to avoid capital gains taxes if the company’s corporate form and structure allows for “rollover” treatment of selling proceeds into a group of qualified replacement securities, known as 1042 securities. This benefit can result in a permanent deferral of capital gains tax if the proceeds are retained in the owner’s estate upon death.

In the case of an S corporation, the portion owned by the ESOP is exempt from federal taxes as a result of the ESOP’s status as a qualified benefit plan. Therefore, once the company is 100% ESOP owned, the company will no longer pay income taxes. This additional cash flow might justify a higher value to the ESOP than to other buyers.

Do Employees Become Entrepreneurs as a Result of an ESOP?

Whether or not employee productivity increases when employees own the business is a subject of continuous debate. Unless there is a reduction of some other compensation or benefit, employees do not give up anything to obtain ownership. In essence, the employees get both – their compensation program and some stock, which has value when they leave the company. Where valued by ESOP participants, the ESOP is really thought of as extra compensation.

One study is often referenced in support of ESOP companies. The study shows that ESOP owned companies earn a small differential (3-5%) more profit than comparative non-ESOP owned companies. Despite the difficulty in assessing comparative businesses, even accepting the differential as fact would not justify the economic differential of giving shares to the ESOP.

Loss of Control

ESOPs are subject to Department of Labor (“DOL”) and federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (“ERISA”) regulations and, therefore, bring heightened regulatory oversight and loss of financial flexibility. The rules are very rigid with regard to employee inclusion in decision-making. In this way, an ESOP is a real partner, not a sham. Decision makers for the ESOP are often times elected or alternatively an outside fiduciary is contracted to provide oversight and vote for the benefit of the ESOP beneficiaries.

When decisions require a shareholder vote, the non-ESOP owner(s) will find that his or her partner is governed by DOL and ERISA rules and regulations. In a decision to sell the company to a third party, the ESOP trustees will ultimately determine if the offer price is fair and pass-through voting rights will inure to all shareholders, including ESOP participants. As a result, many additional decision-makers are included in the sale process.

A Continuous LBO

The sale of stock to the ESOP in a leveraged transaction requires the company to borrow money. An ESOP that buys additional stock will need to borrow money for each purchase. One would think that once the ESOP owns 100% of the company and pays off its debt, that would be the end of it. Instead, vested employees begin to retire or depart and need to be bought out. The company is obligated to provide funds to the ESOP to buy out each employee after they leave the company. As time rolls on, the employee base continues to churn, with each person selling its shares back at market value. In essence, the company engages in a continuous leveraged buyout. This characteristic sometimes comes in conflict with the capital needs of the business.

Why Would One Sell to an ESOP?

Many ESOPs are structured to achieve the goals of the selling owners, taking advantage of the federal tax support of this type of transaction. Anecdotally, we have observed a number of transactions in which the sale price to ESOPs has been higher than likely could be achieved in a sale to a third party. The existence of a valuation report doesn’t appear to protect against that event.

In some circumstances, employees are the only, or at least the most logical buyer of the business. This is most likely true for professional service companies (e.g., engineering, consulting, architecture businesses) or contractors where people are the primary assets. In these cases, the ESOP creates an economic incentive for employees to remain with the company, reducing the inherent cost of turnover and thereby helping retain the company’s most valuable assets. Also, because these types of businesses don’t require significant ongoing capital investment, committing cash flow to buying out retiring employees does not overly constrain the business.

Sales to the most logical buyer can be accomplished without the use of an ESOP, but when the employee base is the most logical buyer, taking advantage of the tax code to make the transition easier makes sense to all parties.