Most M&A transactions involve a discussion around adjustments to EBITDA. These adjustments to a company’s reported financial statements are made to better reflect the true expected performance of the business. When used appropriately, these adjustments are a valuable tool for helping a buyer and a seller understand the real economic performance of the business and therefore avoid misunderstandings that could get in the way of a deal reflecting true fair market value. In essence, these adjustments create a transparent view of what is really happening. When used incorrectly, these adjustments create a lack of transparency, can cloud understanding and lead to a loss of credibility and a gap between a seller’s valuation expectations and a buyer’s willingness to pay.

Over the past several years, we have observed a gradual increase in the number and magnitude of proposed EBITDA adjustments relative to a business’ actual performance. While some of these adjustments are rational and defensible, others are not. Walking the line between defensible and aggressive adjustments is a risky game. Every seller wants to present performance in the best light, but moving too far from reality projects an image to buyers as to expectations and reasonableness in getting a deal done.

Adjustment Categories

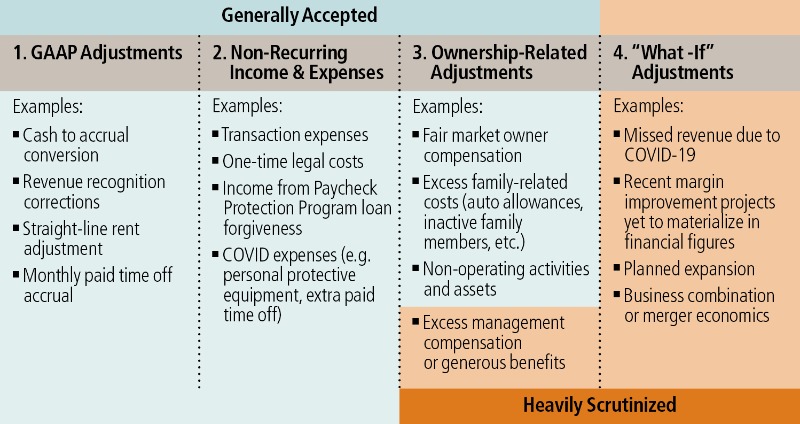

Broadly speaking, EBITDA adjustments can be categorized into four main buckets:

- GAAP Adjustments: Adjustments to conform a company’s financial statements to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)

- Non-Recurring Income and Expenses: Adjustments to remove any income or expenses from one-time events.

- Ownership-Related Adjustments: Adjustments to remove owner-related and non-business related expenses that are unrelated to the generation of revenues and profits and, therefore, would not continue post-closing.

- “What-If” Adjustments: Adjustments to convey what performance would have looked like under different operating and market condition scenarios.

As you make your way down the list, the adjustments become increasingly more hypothetical and there is less empirical evidence to prove the case. In the years leading up to 2020, we saw an increasing level of creative and aggressive adjustments within categories three and four. When these adjustments stray from true expected performance, they become counter-productive to the original purpose of EBITDA adjustments.

The COVID Adjustment

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, a whole new “What-If” adjustment came to life: the COVID adjustment.

Many have become familiar with the term “EBITDAC”, or Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, Amortization, and COVID. The idea behind this calculation is to understand what a business’ performance would have looked like had COVID not occurred. This applies to both businesses that were negatively impacted by the pandemic, as well as to those that benefitted.

There are two sides to the COVID adjustment: expenses, and lost revenue. The expense side of the adjustment tends to be more defensible, and includes such costs as personal protective equipment, extra paid time off, hero pay, and more. As we discussed in our recent article, “Deal Making in a Pandemic”, this portion of the COVID adjustment is generally accepted by the market. COVID revenue adjustments, on the other hand, receive much more scrutiny and are often heavily discounted or disregarded entirely. It can be difficult to accurately assess the exact missed revenue (and EBITDA) associated with the pandemic, and how that missed revenue may impact the next few months and years.

Determining Defensible Adjustments

So, how does one determine adjustments that will be accurate and accepted by the market, while also capturing full fair market value? By always coming back to the original purpose, which is to adjust reported financial performance to reflect the true expected performance in the ordinary course of business. Each adjustment must be examined under this lens.

Quality of Earnings (QOE) analyses have long been performed by buyers to validate seller-proposed adjustments and to identify adjustments that may not have been brought to light. This analysis is typically performed by third-party accounting experts who can review both the GAAP accounting and the less-concrete adjustment categories. The output of this analysis, a QOE Report, can be a crucial piece of diligence information for buyers and their financing sources.

The past several years have seen a rise in the use of sell-side QOEs, in which the seller commissions an accounting expert to assist in identifying and quantifying appropriate adjustments. When done well and used correctly, a sell-side QOE can improve market confidence that the adjustments are accurate. When a sell-side QOE is involved in a transaction, we tend to see fewer “creative” adjustments, and more data and analysis in support of each adjustment. The resulting adjusted EBITDA numbers in turn receive more acceptance in the market.

Staying True To The Purpose

The increased prevalence of adjustments to reported financial statements and the creativity of those presenting the adjusted performance is, in our opinion, moving away from the original purpose of these adjustments. It is not a game to see how creative one can be to produce an improved income statement. Buyers want to know the truth about how a business they are considering buying performs and will perform in the future. Sell-side QOEs are intended to give credibility to an argument that there are discrepancies in the actual statements that do not reflect the underlying economics of the business. When presentations deviate from that simple objective, trust is lost as a result of the perceived unreasonable nature of the claims and the length of the due diligence process lengthens, as buyers find the need to dig deeper to find out what is not being shared accurately. Eventually, each claimed adjustment will be evaluated within the original context of measuring real economic performance, but in the process, there may be unexpected costs of time and lost opportunity.