“I rob banks because that’s where the money is.”

Slick Willie Sutton, famous bank robber

Privately held companies have the advantage of being able to have a long-term focus on value creation. However, our experience is that most businesses focus on the near-term and, for budgeting and planning, the forecast period is short. What might not be appreciated is that most of the value of a business is based on what occurs beyond the forecast period. The purpose of this article is to suggest that business value can be enhanced by taking actions today that will increase the probability of a stronger market position and more competitive business model down the road – that’s where the money is.

Valuation Theory Revisited

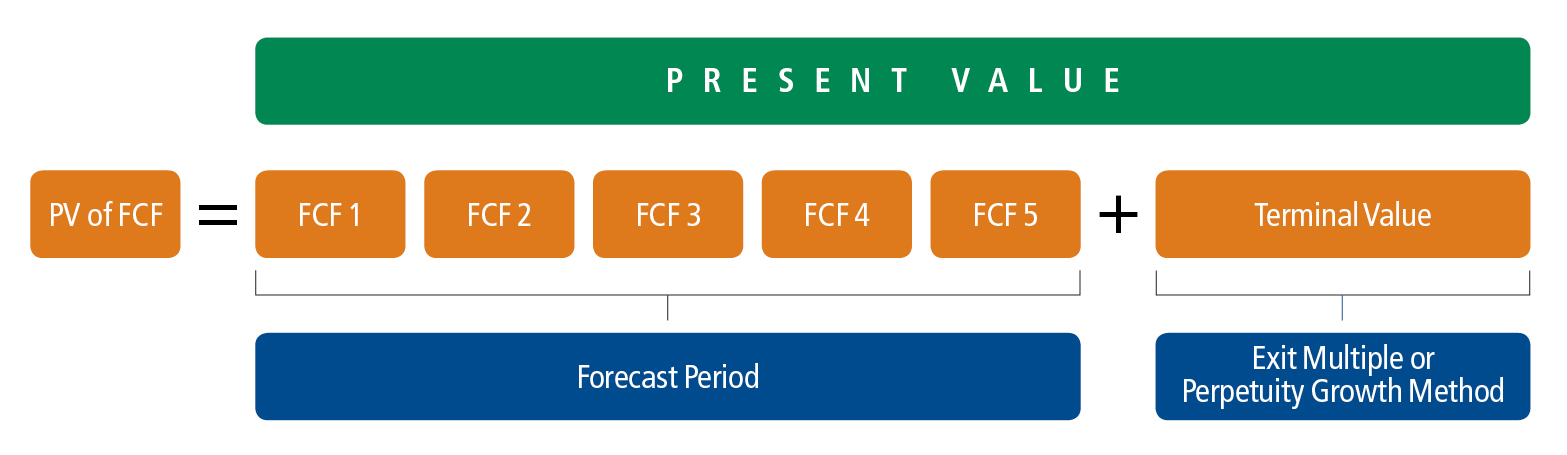

The value of any business is the present value of its future cash flows, discounted using an appropriate rate of return for the risk employed. To calculate this value, business analysts must forecast the cash flows of the business over time. As one moves further from the current period, predictability decreases and accuracy becomes difficult. Because of the near impossible task of forecasting for an extended period, most valuation models calculate the cash flows for a set period (generally five years) and then perform a terminal value calculation to approximate the longer-term cash flows.

We find that the majority of analysis tends to be concentrated on the forecast period, with businesses (and analysts) supporting their work with robust models and detailed assumptions that have been evaluated from a number of angles. These forecasts represent the time period for which we have the most reliable information, but in actuality, the majority of the value of the business actually lies outside this forecast period in the terminal value.

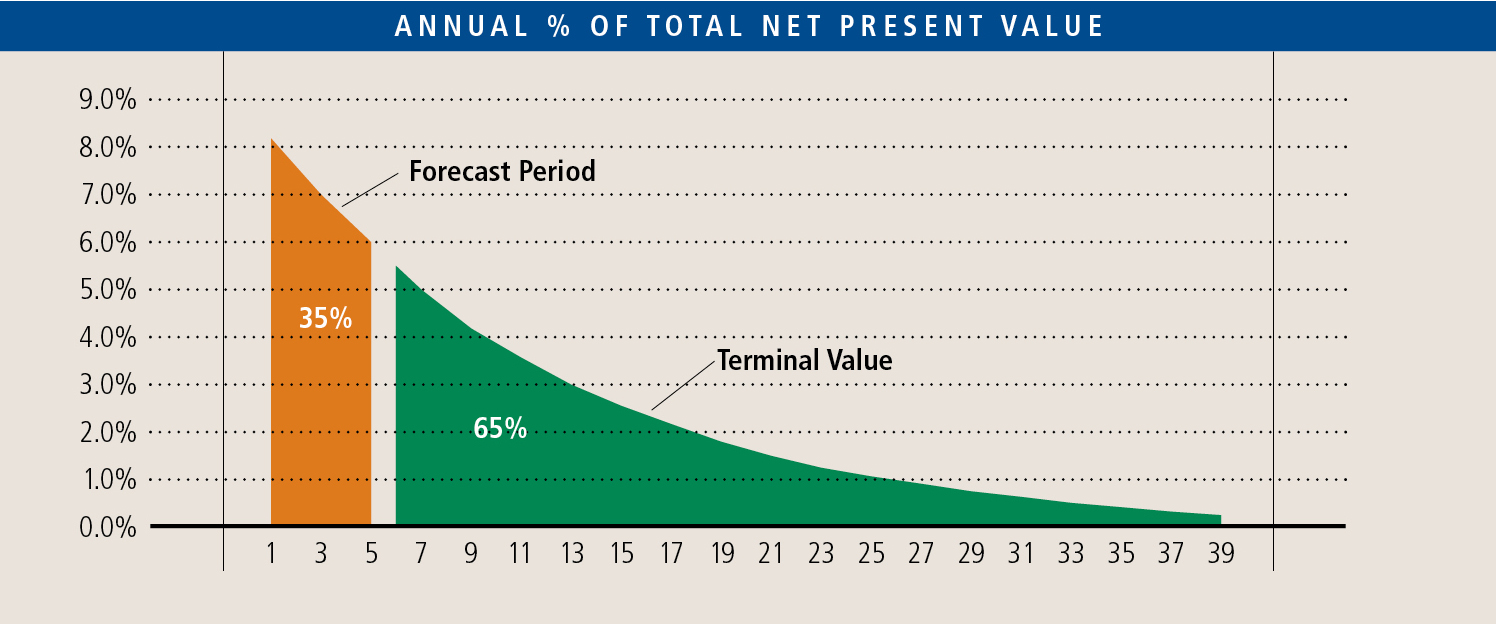

Take for example, a business growing at 3% annually with a 10% cost of capital where the actual cash flows have been mapped over a 40-year period (a decent approximation of perpetuity).

Clearly, due to the time value of money, near-term cash flows in the forecast period are more valuable than later ones, but the forecast period only accounts for 35% of the total present value, while the perpetuity value, accounts for 65%. Extend the forecast period to ten years, and the perpetuity value still accounts for 55% of the total value.

Calculating the Terminal Value:

Terminal value is calculated using one of two methods: the perpetuity growth method or the exit multiple method. In the perpetuity growth method, which is used most commonly, cash flow in the year immediately following the forecast period is effectively capitalized by the difference between the cost of capital and the long term growth rate. In the exit multiple method, which is used less commonly, terminal value is calculated by applying an LTM multiple in the final period of the forecast to the relevant Company metric, usually EBITDA or free cash flow.

Both of these methods are widely used and accepted in the finance community but the nature of simplifying the difficult task of forecasting leads to limitations that need to be considered in any investment or operating decision. The growth method inherently implies that the business thereafter will be steady and will indefinitely earn its cost of capital, a condition that in a dynamic business world will rarely occur. Naturally, this model is very sensitive to the growth rate employed. The standard practice is to choose a rate that is somewhere between inflation and GDP growth, but depending on the stage of the company and when it may actually reach steady state, this may not be appropriate.

The exit multiple method, on the other hand, is a relative valuation, heavily dependent on multiples derived from comparable firms or transactions. While these are acceptable valuation techniques, when applied to a DCF, there is no longer an intrinsic measurement of value. This type of shortcut might make sense when modeling a leveraged buyout, which will likely be sold based on a multiple in the future, but it defeats the purpose of performing a DCF, which by nature is intrinsic.

Given the importance of the terminal value, we wonder why so little attention seems devoted to it in valuation exercises. While we have no issues with the formulas themselves, and certainly understand the need to simplify the estimation of cash flows in the out years, we find that in most valuation exercises, the calculation is merely reflexive, and in some cases, assumes the answer. If the growth method is being used, than an analyst will use GDP, and if the exit multiple method is used, than the exit multiple will be set to the entry multiple.

Why is this important?

As advisors to closely held businesses, we do not advocate our clients lose sleep over how terminal values are calculated, but we do encourage business owners to consider the drivers of long-term growth that will directly impact value today and to take the necessary steps to drive value in the future. One way to think about this is to consider how their business will be evaluated at the end of the forecast period, when the current terminal period becomes the new forecast. Will the factors that drive the current terminal values (opportunities to expand, ability to sustain margins, competitive environment) still warrant the assumed exit multiple? This can only be the case if the next forecast period has the same opportunity for growth as the first, a scenario that is in no way guaranteed given the dynamic nature of markets and businesses.

Likewise, the long-term growth rate is not a fixed variable impervious to today’s actions. Rather, it is directly influenced by decisions made today. Investments in technology, equipment, people resources, and business systems may look like expenses that bring down current profitability, but could result in a much stronger long-term competitor in its industry. In valuation terms, those investments can enhance the growth rate in the terminal value.

While it is always difficult to take a long-term view (in the long term we are all dead), the majority of the intrinsic value is in the terminal value. When the terminal value accounts for the majority of intrinsic value, the ability to increase the long-term growth rate will have a definitive positive return to the business owner.