Businesses often claim to sell a “branded” product—food, consumer product, service, material, or other category. The implication to them is that the brand causes the business to deserve a premium valuation over what would otherwise be achieved by evaluating the economics of the business. In other words, the existence of a brand connotes value beyond sheer numbers. The truth is that every business has a brand, but not every brand is premium. And, it is always about the numbers.

What is a Brand?

Many owners and business managers think their brand is their product, logo, website, name, or packaging. These attributes contribute to and help communicate the brand, but they do not constitute a brand in and of themselves. A better definition is the following:

“A brand is the short-hand representation of the customer perception of the promises made and kept with regard to an organization’s product and service attributes.”

For a brand to exist, several things must be present: the product or service must be perceived to occupy a defined space on the price quality spectrum; the product or service must be represented either visually or experientially; and the customer must recognize the visuals or experiences and the value they represent. Without all of these components, a brand doesn’t exist.

An effective brand is one that clearly communicates an advantageous value proposition that the customer recognizes. Bad brands tend not to have longevity because the perception of a negative product or service experience does not lead to an abundance of customers. On the other hand, good brands engender a specific value proposition that coincides with a solution to a problem sought by the customer. Belief that the proposition is rare and consistently reliable creates a match that fosters loyalty.

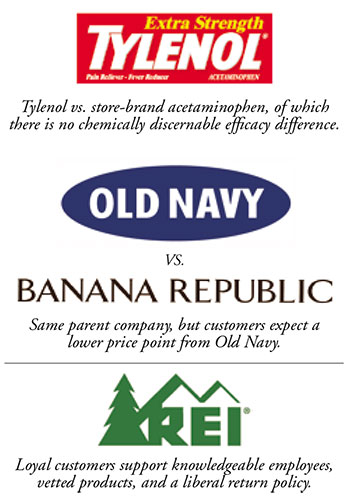

A good brand simplifies the customer purchase decision, thereby closing off customers thinking about alternative solutions. A brand can simplify the customer decision in a number of ways: presenting a known quantity against an unknown quantity (such as Tylenol vs. store-brand acetaminophen, of which there is no chemically discernable efficacy difference); communicating price point (a customer would expect a lower price point at Old Navy than at Banana Republic, even though the parent company is the same); or communicating nonprice benefits, such as service level (REI stocks similar products as other outdoor equipment stores, but knowledgeable employees, vetted products, and a liberal return policy have supported loyal repeat customers).

Is the Brand Valuable?

Presuming that the brand engenders positive loyalty, the degree of brand value depends upon whether the product or service model solves problems for a large enough market at a price that allows the brand owner to generate attractive profitability.

The accounting for brand value and the methodologies for calculating brand value are widely debated. Brand value methodologies have largely been a financial exercise, often with the purposes of replacing goodwill as an asset class, or to justify cross-tax jurisdiction license arrangements to funnel taxable income to the lowest tax jurisdiction. Methods such as a “market approach” (comparing the sale of comparable brands), royalty relief (estimating a capitalization of the royalty stream that one would have to pay to license the brand), a cost-based approach (the sum of the marketing and advertising costs incurred to develop the brand), and the economic-use method (the difference in the business with and without the brand) all have thought behind them, but each has the philosophical problem of implying that the brand is a “thing” that has a defined and distinct value.

When viewed in its holistic definition of the expression of the customer experience with the organization, the value of the brand is not independent from other assets of the business. Rather, the brand is the external representation of the culture of how the organization utilizes its human and capital resources to provide a defined and reliable customer experience. As such, there are pricing and cost implications to how the customer promise is delivered. Brands don’t have a specific value; they are an integral part of what generates the profit stream. Ultimately, a valuable brand is one that contributes to abnormal amounts and longer expected durations of profit as a result of connecting with customers such that loyalty barriers are created.

We think that brand value discussions are merely a subset of a broader discussion of corporate strategy. “Brand” is the result of communication to both internal and external business audiences of the critical value proposition and promises of the organization to its customers.