Bigger isn’t always better. The assumption that a company growing revenue, assets, employees, and profits becomes more valuable to its shareholders requires closer examination. Growth creates value only if adequate compensation exists for the incremental capital required to generate that growth. Focusing on where and how a business earns an adequate return on the capital employed, even if that means shrinking the business from a revenue or asset perspective, can create more value. Managers commonly focus on EBITDA growth, giving little consideration to the amount of capital required to achieve that growth. Ensuring that growth-oriented projects achieve acceptable returns should trump other decision criteria.

In previous editions of IN$IGHT, we have discussed the concept of Economic Value Added (EVA), which quantifies in absolute dollars the value contributed to the enterprise during the measurement period. Whereas EVA measures value creation in absolute dollars, return on invested capital (ROIC) measures performance in relative terms. Compared to the return required to adequately compensate for the risk of the investment, ROIC offers a compelling metric to evaluate the employment of capital.

ROIC measures after-tax operating profit relative to the average amount of capital invested in a business. Although still a shorthand measure of performance, ROIC’s advantage over other measures such as return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) is that ROIC accounts for capital provided by all investors and focuses on the net investment in the business. For example, the performance of local businesses like Amazon.com and Costco, which operate with negative working capital, would be vastly underappreciated by ROA. Likewise, ROE presents a bias towards a leveraged capital structure, ignoring the financial risk resulting from increased debt. ROIC recognizes efficient capital management and provides owners and managers with a clear measure of performance agnostic of capital structure.

The Levers

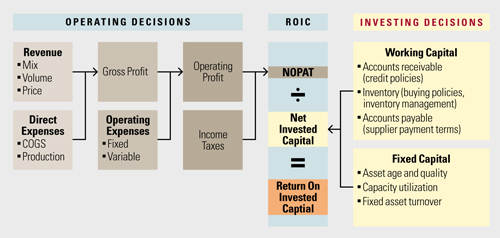

Maximizing ROIC requires an understanding of its levers. The ROIC “tree,” presented nearby, delineates the core constituents of return and invested capital. Many operating and investment decisions that influence ROIC are easily within the reach of managers.

Operating decisions influence the income statement. Because ROIC accounts for capital provided by debt and equity sources, the relevant metric is net operating profit after tax (NOPAT). Therefore, increasing revenue, decreasing input costs, shifting product mix to higher margin items, or decreasing operating expenses all favorably impact ROIC.

Investing decisions influence invested capital (working capital and fixed assets), which is the denominator in the ROIC calculation. Whereas changes in revenue and expenses are more visible through the flow of an income statement, fixed and working capital investments are measured as of a given date on a balance sheet, and therefore their impacts might not be as obvious over time. Improvements in net operating working capital – such as increased inventory turns, more rapid receivables collection, and optimized fixed asset utilization—directly impact ROIC by reducing capital investment.

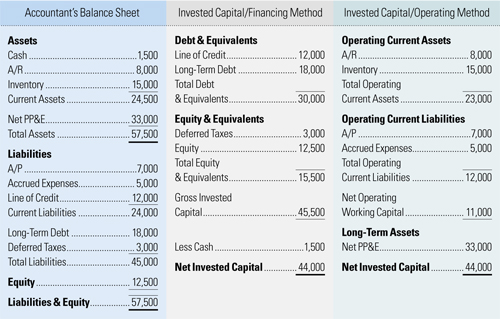

By making a few adjustments to the traditional accountant’s balance sheet, invested capital can be viewed from either a financing or operating perspective. The financing perspective sums all net debt and equity capital, making sure to include capital equivalents like unfunded pension liabilities and deferred tax liabilities. The operating perspective, however, describes how those capital contributions have been invested, measuring the net difference between operating assets (A/R, inventory, net fixed assets, et cetera) and operating liabilities (A/P, accrued expenses, et cetera). The table below illustrates the link between the two methods.

An Example

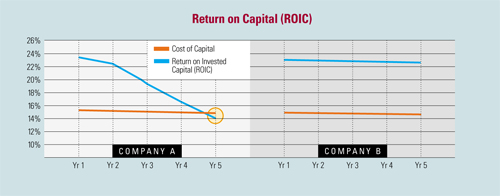

What happens when managers focus on growth in sales and profit without regard for the associated investment? Consider the following two companies. Both currently generate $10 million in NOPAT with $44 million net investment in operating capital. To make the example simple, each company is valued based on continuing its current performance, resulting in initial valuations of $66.7MM ($10MM NOPAT/15% Cost of Capital, or the inverse, 6.67x NOPAT).

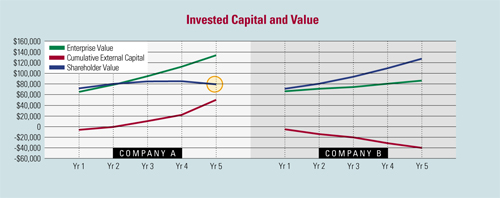

Company A pursues a strategy to grow NOPAT, regardless of the investment required. To accomplish that, management begins relaxing credit terms to entice incremental sales, stocks increasing amounts of inventory, and orders new equipment in advance of projected revenue growth. Company B, on the other hand, pursues only high-ROIC projects, which result in lower revenue and profit growth. The above graphs illustrate the economic impact of these strategies.

The shareholder value curve presents the results of each strategy. Company A’s focus on NOPAT growth requires substantial external capital. Company B, however is able to finance its growth internally (through operating profits), enabling the owner to extract capital from the business (represented by the downward-sloping cumulative external capital curve). Thus, although Company A has grown larger as measured by enterprise value, the owner of Company B is far wealthier as a result of the growth, the lower capital requirements, and receipt of distributions. By the 5th year, the additional capital required to fund Company A’s aggressive growth campaign has dragged the Company’s ROIC below its cost of capital, resulting in a decline in shareholder value.

Growth can create shareholder value, but business owners must be cognizant of the implications that strategies solely focused on growth have on the balance sheet. In other words, growth strategies must be rooted in expectations for adequate returns on the capital employed. ROIC provides a clear and comparable measure of performance that recognizes that all cash flows are not created equal. Managers that are mindful of ROIC while evaluating growth strategies will increase the chances of generating real economic value in their businesses.