Industries and the companies within them are dynamic. They are constantly changing and evolving as a result of innumerable internal and external factors. A business owner may know this instinctively, but often as a backdrop to the day-to-day challenges of running a company. Imagine his surprise when he hears that a business similar to his own has sold, and over cocktails at the country club, the truth comes out that the valuation multiple of the other business was almost double what he had previously expected for his own company! Surely he could expect the same multiple, right? Maybe not.

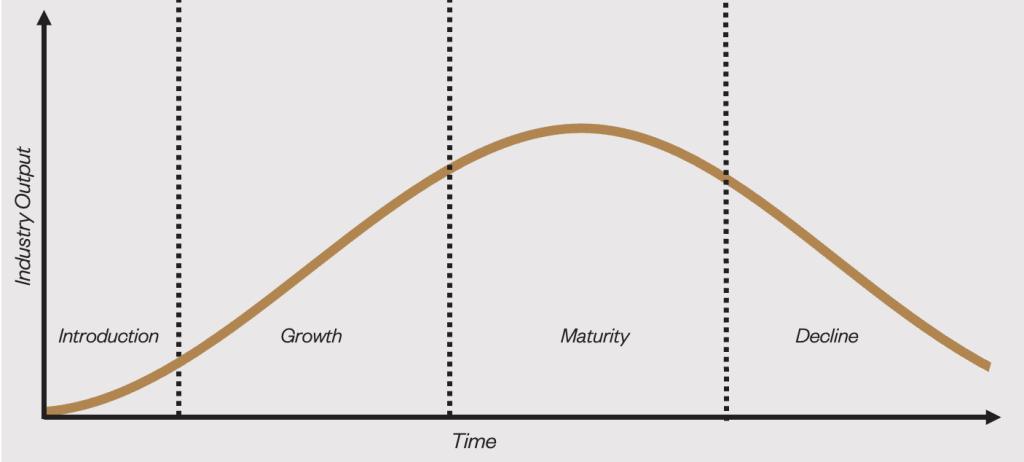

Most industries follow a common lifecycle that begins with introduction and then moves through growth, maturity, consolidation, and eventually decline. That textbook industry cycle typically relates to an industry’s ability to efficiently match output with demand. But beyond the output lifecycle, a business owner needs to be aware of where the industry sits in its valuation cycle, which is not the same thing.

We have written on valuation many, many times. Without being reductive, a business’s value is based on the future cash flows it can produce, discounted to today’s dollars on a risk-adjusted basis. That approach represents a company’s intrinsic value. Fair market value, on the other hand, is simply the most that a buyer would be willing to pay for the business at a point in time. In many stages of the industry lifecycle, intrinsic value will roughly equal fair market value. The two should be related, after all. However, there are often inflection points where investor interest and excitement causes a temporary disconnect between a company’s intrinsic value and its current value on the open market. We refer to these periods as valuation bubbles.

It can be an easy trap for a business owner to believe that a sudden increase in relative valuation of the business is a permanent shift, when instead, it is a temporary effect of the dynamics of the broader market. Having the self-awareness to understand when an industry is in a valuation bubble, and when to act on that knowledge, can allow an owner to capture the greatest value.

Historical Examples

Valuation bubbles have occurred in dozens of sectors, some more notable than others. History provides a framework for understanding when bubbles form and burst. A few notable examples:

British Railway Mania in the 1840s

From 1843 to 1845, investors poured capital into railway projects, doubling the prices of railway shares and leading to thousands of new projected railway lines. Values became inflated far beyond intrinsic value, partially as a result of inflated long-term expectations and the availability of leverage allowing investors to acquire shares in installments. The bubble burst rather quickly, leading to a sustained industry downturn.

Waste Management Services in the 1990s

The local and regional waste hauling sector saw a massive wave of consolidation, fueled by scarcity and investor excitement over the sustainability of current performance. We experienced this firsthand while representing several family-owned waste hauling businesses in the Pacific Northwest. It was common back then for an independent business to receive a valuation as high as 20x EBITDA or more. Public valuations reached an average of nearly 18x in 1996 before falling in 1999. After that, average public valuations did not reach above 10x EBITDA for 17 more years.

Bubble Attributes

Analyzing these historical occurrences and others like them reveals some common themes that help us better predict future risks. A theme in almost every case is significant market fragmentation. Fragmentation means that as capital initially rushes into the industry, there are ample opportunities for that capital to target.

In early-stage growth markets, the bubble can be irrational, or at least heavily driven by the fear of missing out. In a more mature consolidation market, larger acquirers have run out of opportunities to grow organically and have turned to acquisition as the primary driver of growth. If the acquirers are publicly traded, they know what their relative valuations are, and any acquisition that drives accretive earnings is a net positive. As there are fewer and fewer attractive candidates, the acceptable price paid can drift higher and higher toward the accretive threshold. This can mean high valuations for a period of time.

Related to fragmentation, another theme is the presence of roll-ups relying on multiple expansion. When multiple acquirors are targeting a sector to roll up small companies into a larger platform, those smaller companies become viewed as critical elements to the success of the investment thesis. A private equity buyer can justify paying 12x EBITDA for a small business, even if that business was historically valued at 6x EBITDA, as long as it believes the larger platform will eventually sell for 20x EBITDA. That in and of itself is not irrational behavior by the buyer. However, the conditions for that to be a rational approach have a ticking clock on them, as there may soon be no buyers willing to pay 20x for the larger platform if the underlying business or industry economics can’t support that valuation, which itself has to be built on rapid growth in order for the numbers to work.

As it is necessary to target fragmented markets or pursue a roll-up, capital availability is another critical driver of consolidation bubbles. Huge influxes of capital targeting a sector will drive up demand and valuations as everyone competes for an increasingly limited pool of opportunities.

Cautious Excitement

If you are a business owner in an industry experiencing significant valuation increases, it is tempting to celebrate—but caution is prudent. On the one hand, you might be able to achieve a valuation that the same business owner 20 years ago could never have dreamed of. On the other hand, if you fail to see the warning signs before the music stops, you could watch a large share of your net worth disappear over nothing more than bad timing. That does not mean that we are saying the answer is always “Get out now!” That would be poor and shallow advice. Instead, we advocate that you should understand the transience of these valuations and have a plan in place for how and when you are going to take advantage of them.

Warning signs pop up from time to time, but they are rarely obvious before it is too late. Some common signals include:

- Spikes: Sudden, dramatic increases in industry valuations should be viewed as a yellow light. It can be exciting but proceed with caution and make sure to look into why that is happening.

- The Comparison Game: When valuations are attributed only to the fact that someone else paid a similar or lower price for a similar business, it is a signal that investors may be moving away from valuation fundamentals.

- Multiple Arbitrage: When the intended aim of a transaction is buying something to aggregate it with other like businesses and then selling the larger bundle at a higher price, without much (if any) change to the actual operations of any of the aggregated businesses.

- Falloff: A slowdown in consolidation after a period of rapid transaction activity may mean the end is in sight or perhaps has already arrived.

- Widening Spread: If you take the time to understand your business’s intrinsic value, you can keep an ear out for when valuations start to trend far above that. A bubble may be brewing, and if a legitimate offer comes to you at that higher price, real consideration is warranted.

Each industry is unique, and so is each business and owner within that industry. The right timing for your competitor may not be the right timing for you. The important thing is to be aware of the bubble and understand why it is occurring, be vigilant about watching for warning signs, and be prepared to act with minimal warning when the time comes.