Introduction

Employers in industries with unionized labor forces are likely familiar with and may be involved in some sort of multiemployer pension plan (“MEPP”). These plans, which involve several employers combining to offer retirement benefits to their employees, are common in industries with high labor portability, such as construction, transportation, or hospitality, where employees desire to move among various employers in a union while continuing to accrue and receive retirement benefits.

MEPPs were first introduced under the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, also known as the Taft-Hartley Act. MEPPs are collectively bargained and maintained by multiple employers and a labor union. According to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (“PBGC”), there are approximately 1,400 active defined benefit MEPPs in the United States covering more than 14 million active workers and retirees.

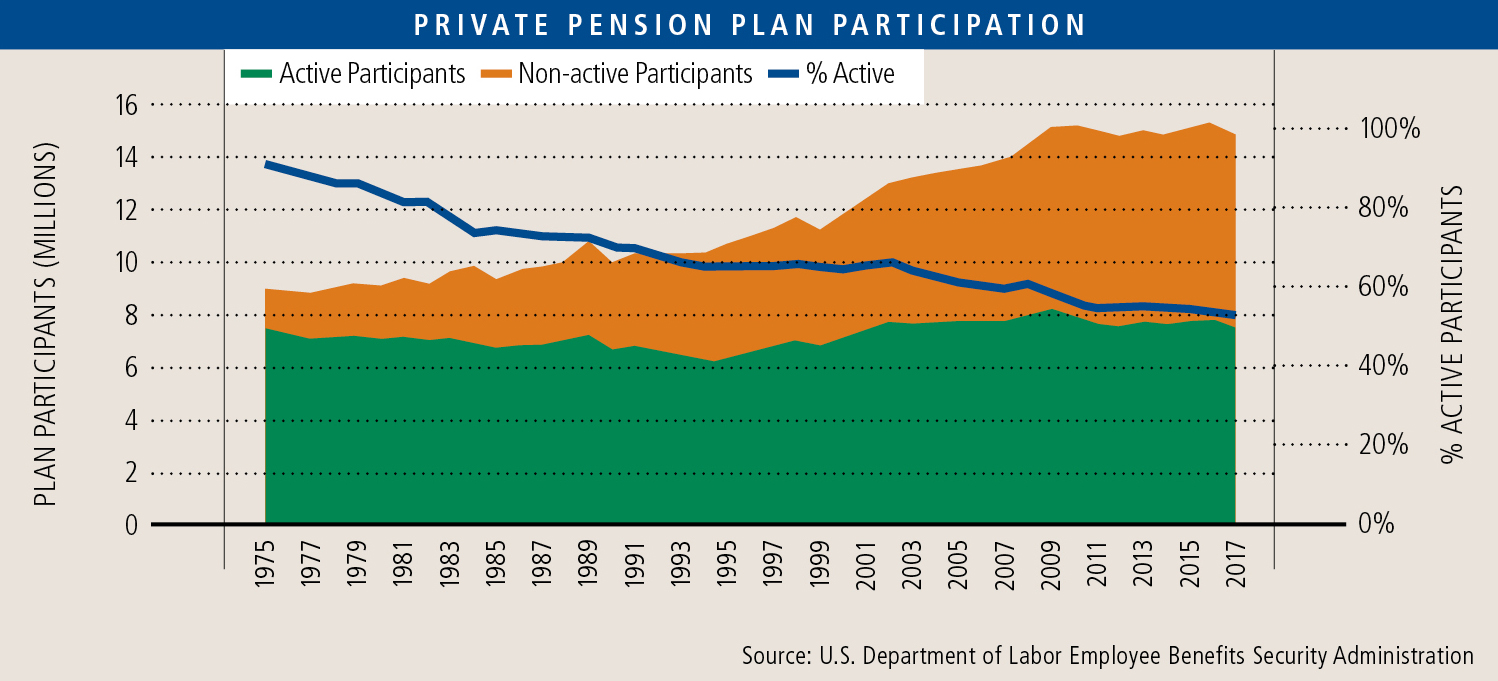

The number of active workers in MEPPs has held steady at approximately seven million since 1975, while retirements and increasing life expectancy of retirees have led to a significant increase in total plan participants over that period. This trend has created a mismatch between the number of employees contributing to the plans and the number drawing benefits.

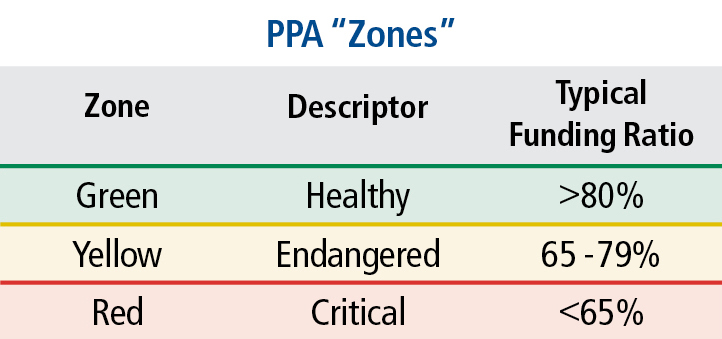

As a result of this mismatch, guaranteed fixed benefit streams to participants, and poor investment returns on plan assets, many defined benefit MEPPs have become underfunded and do not have sufficient assets or contributions to cover projected outflows. Congress passed the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (“PPA”) in an attempt to address the significant funding deficits of many MEPPs. In addition to creating additional remediation steps for underfunded plans, the PPA established three categories (“zones”) of plans to help participating employees and employers to quickly understand the funding status and overall risk of their plans. These zones are based on a plan’s funding ratio, or the ratio of total plan assets to liabilities.

Despite the additional remediation steps permitted by the PPA, the PBGC estimates that 10-15% of MEPP participants are in plans still considered to be “critical and declining” with insolvency expected within the next 20 years.

As a participating employer in a MEPP, there are three distinct obligations that business leaders must be aware of when considering any sort of M&A transaction:

1) Ongoing contribution requirements;

2) Withdrawal liabilities; and

3) Mass withdrawal liabilities.

Ongoing Contribution Requirements

Employers in a MEPP contribute to the plan each month based on the terms of a Collective Bargaining Agreement (“CBA”) between the employer and the union. Contributions are usually based on the number of hours that each bargained employee works in a given month. Contributions can also depend on the overall funding status of the plan, as red zone plans may enter a rehabilitation phase requiring employers to increase contributions or reduce benefits in order to improve the plan’s funding status and avoid insolvency.

From a transaction standpoint, ongoing contributions are reflected in the cost structure of the business, but the potential liability associated with any underfunding will not appear as a liability on the company’s financial statements, because they are not a sum certainty, instead contingent upon a number of drivers that will vary over time. Typically, the plan’s funding zone (green, yellow, red) will be mentioned in the accompanying footnotes to an Audited or Reviewed statement.

Withdrawal Liabilities

Whether a company is going through an operational reorganization, eliminating union labor, relocating a facility, or considering an M&A transaction, there could be a desire to withdraw from a MEPP. The Multiemployer Pension Plan Amendment Act of 1980 (“MPPAA”) requires employers to pay their share of the MEPP’s underfunded liabilities upon withdrawing from the plan. This requirement, commonly referred to as a “withdrawal liability,” can be a large sum and should be fully appreciated before embarking on any withdrawal process.

To assess the potential liability, an employer can request a formal estimate of the withdrawal liability from the plan or plan administrator. The liability is based on an actuarial formula to determine future expected plan beneficiary payments that incorporates the plan’s funding status, the number of years the company has participated in the plan, and the company’s annual historical contributions to the plan. The formula utilizes the average of the company’s highest three years within the last ten years to calculate historical contributions, so even a company that has slowly phased its employees out of a plan may be impacted by contributions from seven to ten years prior.

Even if there is no intention to withdraw from a plan, any business contemplating a transaction should be aware of the size of the potential liability as buyers will be acutely interested in understanding any obligations they may be inheriting. The estimating process can take 90 days or more and should be initiated as early as possible in transaction preparation.

If a company does withdraw from a MEPP and incurs a withdrawal liability, the liability is typically paid in equal annual installments capped at 20 years. This 20-year cap is key because it limits the company’s overall exposure to any mass underfunding or mass withdrawal scenario (see below).

Once a company incurs a withdrawal liability, that liability will appear on the company’s balance sheet at an amount equal to the net present value of the future liability payments. This is a dynamic equation as the NPV changes over time depending on actual returns and anticipated future returns. In the event of a sale of the business, if the withdrawal liability cannot be retired by negotiating a lump sum payment, the liability will be treated like debt and considered a reduction from enterprise value to determine the equity value in the business.

Mass Withdrawal Liabilities

A mass withdrawal occurs when all or substantially all of the contributing employers withdraw from a plan or cease having an obligation to contribute to the plan. The liabilities for companies in a mass withdrawal are similar to the withdrawal liabilities discussed above; however, there is no 20-year payment cap on the withdrawal liability payments. The same applies to any employers who withdrew within the three years prior to the mass withdrawal. These employers are also considered to have participated in the mass withdrawal and will not receive the benefit of the 20-year payment cap. Due to the potential for an uncapped liability, mass withdrawal liabilities receive extra scrutiny in any M&A transaction. In healthy “green zone” plans, the likelihood of a mass withdrawal is generally low. Red zone plans, on the other hand, are more likely to encounter a mass withdrawal as participating employers begin to view plan insolvency as a real possibility.

As a result, any company planning to withdraw from a MEPP in advance of a business sale should seek to withdraw at least three full years before a sale. This eliminates any buyer’s concern about mass withdrawal liability exposure, thereby improving the risk-adjusted value of the business.

Conclusion

Multiemployer pension plans carry various actual and potential obligations for participating employers. When considering a business sale, diligent preparation is needed to fully understand all risks involved so those risks can be appropriately quantified and communicated to the market. This preparation includes understanding the plan’s funding status, obtaining a formal estimate of the withdrawal liability, and assessing the likelihood of a mass withdrawal.

Buyers tend to view MEPPs as highly risky and may even walk away from a transaction due to perceptions of outsized risks. Business owners should work with a team of legal and financial advisors who have experience handling these issues in a transaction environment, as adequate preparation can go a long way in mitigating any unwarranted buyer concerns.