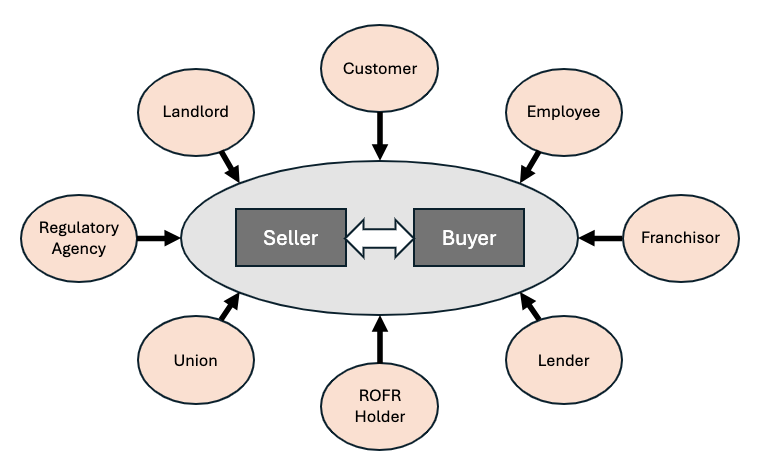

Acquisitions of privately-held businesses are typically thought of as private, highly confidential negotiations between a buyer and a seller. It is true that the majority of the transaction discussions take place among those two parties and their respective advisors. Outside of that small group, however, sits a larger group of third parties that might have an ability to exert their influence over a transaction. The level of influence can range from simply changing the mood around a transaction, to changing who the buyer is, how much they are paying, and whether or not the transaction is allowed to close.

At some point in the evolution of the transaction, the seller and buyer will likely reach a stage where it becomes necessary to bring other third parties into the fold. It becomes especially important when those parties are required to approve a deal before it can happen. Exactly when, and how, those parties are brought into the process should be carefully considered.

Here we highlight some of the more common third parties that have the ability to exert their influence over a transaction, and why that influence comes into play:

Common Examples

Landlords:

Many, if not most, commercial lease agreements include either a Change of Control or Assignment provision to allow the landlord to control the quality and financial capability of its tenant. These provisions require the tenant to receive landlord consent when selling the stock of the business or transferring the lease in the case of an asset sale. While sometimes viewed as a perfunctory approval in the transaction process, landlords may view their approval requirement as an opportunity to improve their position, potentially through an increased lease rate or extended term.

Customers:

For businesses with large or project-specific customer contracts, the agreements may contain transaction approval or notice requirements. After all, if a customer is spending $10 million on a whole new manufacturing system, they might want to know that the system provider is being sold and affirm the quality of the acquiring entity.

Employees:

Key members of the management team are vital parts of any acquisition. The buyer is relying on those employees’ enthusiasm, support, and leadership of the business going forward. Some employees may be so important that their lack of enthusiasm in a transaction may dissuade the buyer entirely. Depending on their attitude about the transaction, employees may use it as an opportunity to improve their role and compensation within the business.

ROFR Holders:

A party holding a Right of First Refusal (“ROFR”) has final say in who the buyer can be. As we wrote in “Getting Past the Right of First Refusal” from 2020, original equipment manufacturers and franchisors often include these ROFRs in their dealership or franchise agreements which allow them to approve the next owner of the business. If they are not happy with the buyer, they have the right to step into the deal and become the acquiror themselves, or assign that right to another party.

Regulatory Agencies:

Depending on the size, geographic footprint, and business nature of a company, an acquisition may require approval from various regulatory agencies. As an example, the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (“HSR”) requires parties to report transactions exceeding certain size thresholds to both the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and the US Department of Justice Antitrust division. If the transaction is determined to be harmful to competition, it could be blocked. Similarly, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (“CFIUS”) has the ability to address national security risks arising from cross-border transactions by blocking or modifying a transaction. There are nuances to determining whether a transaction needs to be blessed by HSR, CFIUS, or other regulatory bodies.

The Court of Public Opinion:

While it may not be a technical approval requirement, the perception of an acquisition among members of the public can be important to both the buyer and the seller. Sellers want their employees and communities to feel good about the outcome, while buyers want those same groups to be supportive through the next phase of the business. Inaccurate or poorly timed disclosures about deal specifics can have a detrimental impact on the public’s support of the transaction, so avoiding premature news is paramount.

Strategies for Mitigating Influence

When considering a transaction, it is critical to take the time early on to think through all potential third party influences, and establish a plan for when and how those parties will be approached. The exact strategy will depend on the relationship with each of those parties, but there are some tools that can be used to eliminate or mitigate the influence.

Beginning well in advance of a transaction, business owners can try to structure important contracts in a way that the contract counterparty does not have a say in a future M&A event. The ideal outcome would be to completely remove any requirements for Change of Control Approvals or Assignment Consents, especially in the case of landlords and customers. Most counterparties will strongly resist the removal of those terms, but may be open to agreeing that the consent will at least not be unreasonably withheld.

Another common approach to reducing third party influence is to make sure all transaction points are fully negotiated and documented between the buyer and seller before pursuing third party approvals. This can be accomplished through a timing gap between the signing of a definitive agreement and the closing of the transaction. The time in between, which could be days, weeks, or months, is then used to pursue the required consents. The benefit to both buyer and seller is that, apart from not receiving these consents, the deal is effectively complete. The more complete the transaction, the more likely it is that the third party will view it as a Yes or No decision, rather than a chance to modify the situation in their favor.

Each third party disclosure should be evaluated in the context of risk. There could be risks of sacrificing confidentiality, sandbagging the transaction, losing a major customer, or experiencing a major disruption to the business. With that risk in mind, you can then weigh the potential costs of the disclosure against the timing of when the disclosure needs to happen. While any disclosure might be uncomfortable, there is a difference between “they won’t be happy when they hear about this” and “they can completely block this from going through.” The more the risk tilts towards the latter, the more important it becomes to effectively time the disclosure.

Each third party should also be evaluated based on the strength of their relationship with the company, and how likely they are to react positively or negatively. Some parties might just want what is best for the business, the owner, and the employees, and would approve the transaction with no issue. Others may be more contentious, particularly if previous negotiations and interactions with that party have been difficult. Then, there are the regulatory bodies such as the FTC and CFIUS that have no relationship with the company at all, and the timing for those disclosures is fairly rigid.

It is never comfortable when transaction discussions move beyond the inner circle of buyer and seller and into the hands of third parties. To maximize the likelihood of success and minimize the risk to the business and transaction, a strategy should be developed specific to each party, with contingency plans in place as needed.