Exclusivity has been a critical component of business transactions in the modern era. Businesspeople have weighed the trade-off between playing competitors off each other and closing in on a binding agreement. Market conditions at the turn of the millennium have made exclusivity a habitual tool for middle market deal professionals. However, upon reflection over our recent experiences, it may be time to dust off the tool and examine when and where exclusivity should be used.

Slicing Both Ways

As part of their freedom of commerce, business owners have the right to discuss a transaction with multiple counterparties at the same time. Signing an exclusivity agreement limits a seller’s right to solicit, discuss, or negotiate an agreement with any other party. This prevents the seller from maximizing value – ideally, buyers would compete for as long as possible. Even worse, after being granted exclusivity, the buyer has all the power in negotiations as the seller is not allowed to negotiate with anyone else, even as a means of keeping the buyer honest.

However, exclusivity brings one major benefit to the seller. Granting exclusivity (typically) increases the probability of getting a deal done. Buyers, after all, need to spend considerable time and money conducting diligence in order to confirm their investment rationale and document a deal. Buyer expenditures during this period can total one to two percent of the deal size. These buyers are concerned they will make a considerable investment to investigating a business only for a third party to “swoop” the deal.

Consequently, buyers have said, “I promise I will give you a big bag of money, but you have to negotiate exclusively with me.” For the past several decades, middle market sellers have decided that this trade-off was worthwhile. Increasing the probability of getting one party to spend money on completing a deal was more important than the possible negative impacts.

Creatures of Habit

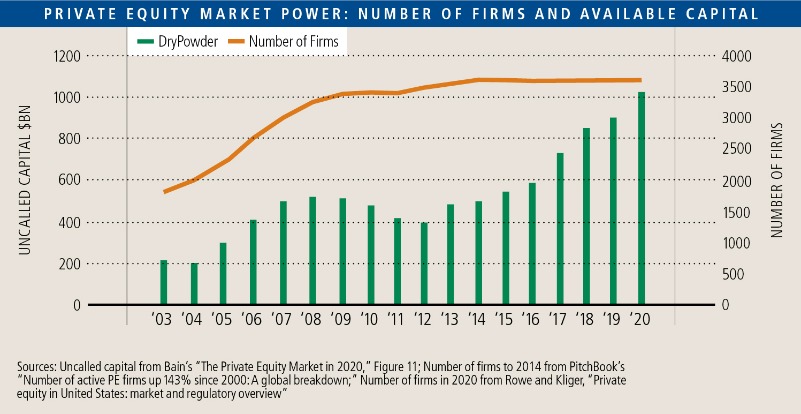

Repeated experience making that trade off caused middle market deal professionals to deem exclusivity an essential transaction tool. By and large, this was a sound decision. As we show in the chart below, in the early 2000s, there were fewer likely buyers, as represented by the number of operating private equity firms, for any middle-market business. Bankers were able to keep track of these buyers. They (hopefully) knew which buyer was good for their word and which to avoid. Buyers with a reputation for promising lofty valuations and then re-trading down were avoided.

The scarcity of buyers also resulted in wide valuation ranges. With only a handful of investors competing in each process, radically different views on value emerged. One buyer might value a business at four times cash flow, whereas another might calculate obtaining spectacular returns at seven times. Identifying the highest-valuing bidder was relatively easy.

Furthermore, the buyers’ opportunity costs of a deal were higher. Because there were fewer buyers than businesses seeking transactions, buyers had the upper hand—they could be picky about which targets to engage. Additionally, diligence was time-intensive for investors. Buyers had to fly out and investigate a business, review physical materials in physical data rooms, and crunch numbers themselves. Every deal a buyer investigated meant they passed on many more for lack of bandwidth.

Finally, deals were done at lower valuations in the earlier years of middle market M&A. Return profiles based on low acquisition multiples gave buyers a substantial cushion in case negative findings were uncovered. A financial buyer computing a 35% return could afford to be less concerned if, for example, IT systems needed more maintenance investment than the seller represented. Because buyers tried to studiously avoid earning a reputation for re-trading, investors were generally good for their word. In total, in the days when the middle market was wildly inefficient, giving up exclusivity made sense because buyers had low incentives to re-trade and there were enormous barriers to getting a deal done.

Then Things Changed

The last decade has seen the development of very different market conditions. The number of buyers has doubled, and the amount of capital has expanded far more (see chart below), as represented by the size of the private equity market. To take advantage of the greater number of alternatives, sellers and their representatives have been running broader auctions. Bankers now know less about the individual buyers they are contacting. In some cases, bankers even contact buyers with less reliable reputations because they are unsure who might bid the highest value.

Consequently, valuation spreads have tightened. Recent auction-sales have become large enough that multiple buyers submit bids indicating similar views on value. Those buyers now have three times as much dry powder as in the previous decade (see chart nearby), so they must compete to put capital to work. The market is now more liquid at the ultimate transaction price.

This new M&A market liquidity, along with data-sharing improvements, has driven buyers’ opportunity cost of a deal lower. Transaction volume has not increased commensurate with the firm count or available capital, which means buyers cannot remain as picky about the businesses they buy. Investors are casting a wider net and investigating more opportunities at the same time, which is now possible thanks to virtual data rooms and legions of transaction consultants. Today, buyers can investigate more deals with less time cost to themselves.

In effect, the pendulum has swung the other way. Buyers now compete so fiercely that deal valuations are at the edge of acceptable return profiles. This puts extreme pressure on buyers to guarantee adequate returns by conducting exhaustive diligence processes. A buyer looking at a 15 or 20% return might break their return profile when uncovering the aforementioned need for additional IT investment. This prompts a re-trade.

Exclusivity Costs are Going Up

The characteristics of the past decade’s market imply that the cost to a seller of exclusivity has gone up and the benefits have fallen. First, a seller likely now has more options near the highest price, any of which might have a different view on the value of diligence findings. The party granted exclusivity in a process today might not have been the highest-value bidder for the business. Second, incentives have changed since buyers appear to suffer no harm from re-trading. Bankers are either overlooking buyers’ reputations or are not aware of them. Some buyers have even made overpromising and then re-trading to nab a below-market deal their core investment strategy. Third, with so much capital chasing so few businesses, from the macro perspective, the probability of getting a deal done is enhanced less with exclusivity. Perversely, because buyers re-trade exclusive deals more frequently, the probability of getting a deal done at the promised price has fallen. In summary, the market has changed, and by acknowledging the new market dynamics, dealmakers can create a new framework about when to use exclusivity.

Sellers and their bankers have tools to navigate these new market conditions, and a future Insight article will help create a new framework for readers to gauge when and how to employ those tools in a sale process.