In the Fall 2017 issue of IN$IGHT, we discussed why “Every Company Needs a Growth Story”. We explained how growth orientation influences company culture, perceived opportunity, and ultimately value.

In their quest to grow, it is not unusual for middle market companies to become fixated on revenues and cashflow as a measure of progress. However, success measured on these milestones alone is likely to be short-lived. In the long run, these milestones don’t matter if the business will not be profitable and the growth itself doesn’t contribute appropriately to profitability. To understand the overall health of the business and whether its growth will be sustainable, one needs to grasp its margin story.

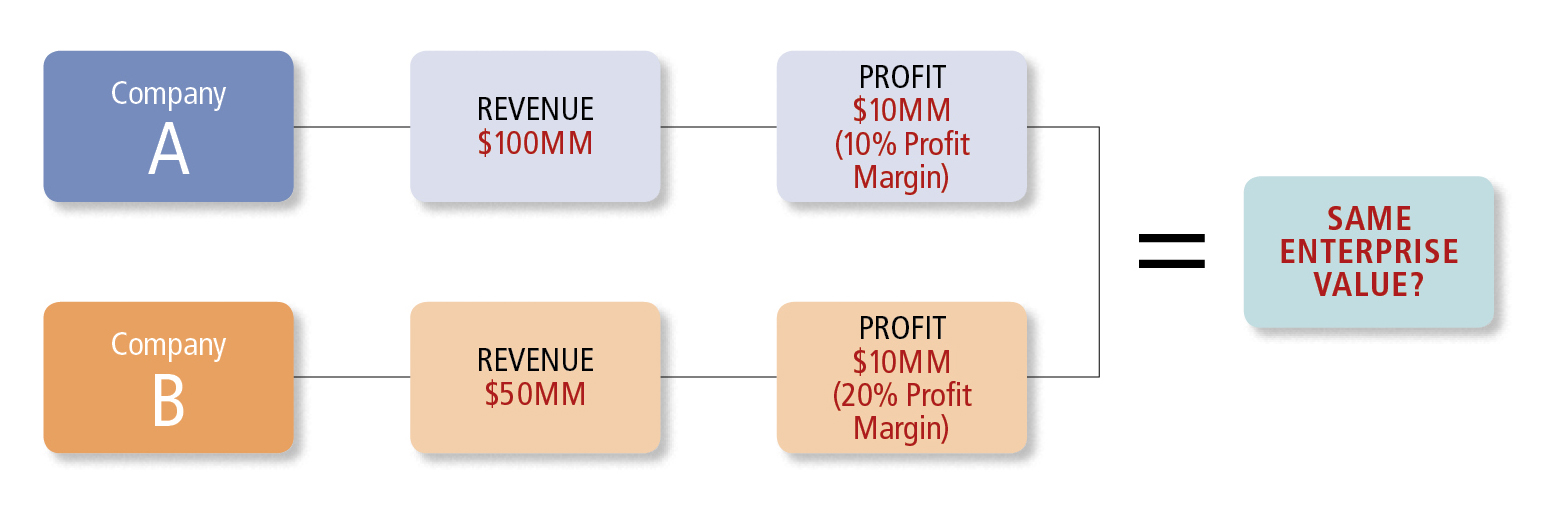

Consider two companies in the same industry that each generated $10MM of profit. The larger company, Company A, accomplished it on revenue of $100MM at a 10% profit margin. The smaller company, Company B, did it on $50MM of revenue at a 20% margin. Application of a “multiple” would yield the same enterprise value for the two businesses, but is that an appropriate methodology? As we will examine, it depends on each company’s margin story.

Gross Margin or Net Profit Margin?

Let’s first distinguish the two commonly used measures for calculating margin. Gross profit margin is a metric used to measure how well any particular product or group of products is performing. The net profit margin, which is based on a company’s total revenue and operating expenses, provides the big picture view of a company’s performance.

Margin profiles vary by industry and aren’t really comparable. A successful large airline might have gross margin of just 7% and net margin just above 5%. Most of the costs in this business are at the operations level and relatively little at the overhead level. By way of contrast, a software business is almost the opposite because once the software is built, the costs of production are low. However, marketing and administration costs in this industry are very high. Therefore, an absolute margin level is less important than the relative level against peers and competitors in the industry.

Margins are Affected by Changes in Operations

Product mix shifts, price increases, economies of scale, and commodity cost declines, among others, are valid reasons for gross margins to change over time. Some of these costs are fixed in nature and can affect gross margins depending on what point in the demand curve the measurement is taken. Most often improvements in margins below the gross margin level are achieved by cutting overhead costs. This is easier to implement but harder to overcome if the support requirements for the business are harmed. Cutting overhead in high growth companies can be counterproductive.

However, All Companies Need a Margin Story

Companies can improve margins in the medium- to long-term if they have a clear strategy. Notwithstanding that generalizations can be dangerous, below are four successful strategies that we have seen work.

- Reduce number of SKUs and rationalize prices. Companies should look at the profitability of each product they offer and consider eliminating the worst performing ones. The resultant capacity can be refocused to increase volume or quality of its remaining product lines. For example, many beer distributors are realizing that only a small number of SKUs contribute to their profits. Underperforming SKUs not only drag down a company’s performance with added labor, occupancy costs, capital costs, and damaged goods losses coming from the added inventory, but also from added sales and merchandising costs to support the effort to move the SKUs. The hidden cost is the fact that in addition to underperforming, these SKUs can cannibalize volume from profitable SKUs.

- Eliminate unprofitable customers. CFOs should periodically analyze the profitability of their top 20 customers by order volume. Even if certain customers deliver large volumes, the cost to serve might outweigh profitability. In such instances, price increases for these customers might be justified, even if there is a risk of losing them. A related problem is dealing with customers that are consistently tardy with payment. CFOs should ask whether the cost of additional working capital needed to deal with these customers should also be factored into pricing decisions.

- Incentivize employees on margins not just sales. Companies should expect its salespeople to deliver not just sales, but profitable sales. When companies start paying commissions on gross margin rather than on sales, the impact can be clear and quick. Salespeople are likely to curtail discounts and refocus efforts on more profitable product lines. During a recent assignment for a contractor involved in commercial construction, we saw dramatic improvements in average job profitability when salespeople were moved to a gross margin-based commission structure.

- Reduce spoilage and waste. Many companies suffer from hidden production issues. They might have manufacturing quality issues and poor forecasting that have the potential to significantly drag down margins. We recently had an opportunity to look closely at numbers of two competing contract food manufacturers—one profitable and one losing money. Since ingredients are the largest cost item in this industry and gross margins are relatively thin, it wasn’t surprising that the unprofitable company had significantly higher wastage during production.

Comparing Our Two Imaginary Companies

All things else equal, the smaller business with the higher gross margin, Company B, would be viewed more favorably by investors. Higher gross margins represent a buffer to economic downturns because of the ability to absorb volume declines and pricing pressure. And, in an expanding market, the implication is that it will take less growth capital to support an additional dollar of profits. Also, in a consolidation with another company where overhead would represent redundancies, there could be a significant opportunity to reduce costs without sacrificing product quality or service to the customer.

However, a deeper dive into each company’s margin story could be instructive. Company B was operating at maximum capacity and additional capacity was very expensive, thereby restricting its ability to grow with its customers. Company B had maximized its margin profile and further growth would come at the expense of profitability. The margins of the larger company, Company A, were masked by recent costs incurred in adding additional capacity. Additional growth for this business would be accretive to margin as utilization of its cost structure increased, representing a bright future of growth opportunity.

The added wrinkle tells us that margins are not entirely dictated by the market. In a competitive environment, prices can be—but how a company chooses to service its customers, which customers it sells to, and how it positions itself relative to its competitors is a function of strategy and management. Thinking deeply about a company’s margin story can lead the way to unlocking additional value.