Business owners are inundated with letters from supposedly eager buyers of their businesses. While flattering, too much faith in an initial offer can lead to disappointment. Understanding the dynamics of a typical deal––particularly how terms and structures unveiled far down the path of negotiation can render an initial proposal unrecognizable––is essential to driving an optimal sale. As usual, we reiterate our common refrain of preparation, information disclosure, and competition to ensure the deal you expected is the deal you get.

Buyers Resist Revealing Terms

Business acquisitions involve far more than just headline purchase price. Buyers typically resist revealing critical deal terms until far down the road of negotiation and due diligence. This is in part because buyers do not initially have the information necessary to provide a more detailed proposal, but also because holding back terms allows them to be dealt with once the seller is “invested” (both literally and figuratively) in the deal. Particularly when dealing with an unsophisticated seller, it is relatively easy for a buyer to create convincing arguments as to why some new piece of information necessitates a (nearly always) less favorable change in the deal.

Besides purchase price, a number of other major deal terms can greatly alter the attractiveness of a preliminary proposal. These are discussed in greater detail below:

- Structure. What proportion of the deal is cash at closing? Is there an earnout, a seller note, an equity rollover, or a preferred position? As we discussed in “To Roll or Not to Roll,” Winter 2018, private equity buyers frequently require an equity rollover, which reduces the cash at closing and is not ideal for owners seeking 100% sales. If there is an earnout, does the seller have control over the actions that will impact its achievement?

- Working capital. This represents a frequent source of bitterness in deals, as owners feel that buyers are “re-trading” to a lower price through higher levels of working capital required at closing.

- Financing. What proportion of the capital will be debt versus equity? Is the deal contingent on sourcing capital? If the seller is reinvesting equity, will that equity enjoy the same terms as the buyer’s?

- Fees and Expenses. Are the parties treated equally in handling transaction expenses? Many private equity firms require the company to pay all expenses of the buyer, but not the seller (when rolling over equity) and commit the company to pay the private equity firm management fees. All of this may be acceptable, but is sometimes hard to swallow when learned at the last minute.

- Post-closing involvement. How long, and in what role, is the seller expected to remain involved in the business? Again, for owners seeking retirement and a 100% sale, preferences regarding involvement after closing can be a rude awakening.

- Keeping the purchase price. How much and how long is the indemnification period? Are there reasonable limits on indemnity obligations? What is the amount and duration of the escrow? How much is the deductible?

- Promises about the business. Are there dangers lurking in the representations required of the seller (see nearby “GAAP, the False Prophet”)?

Hypothetical Example

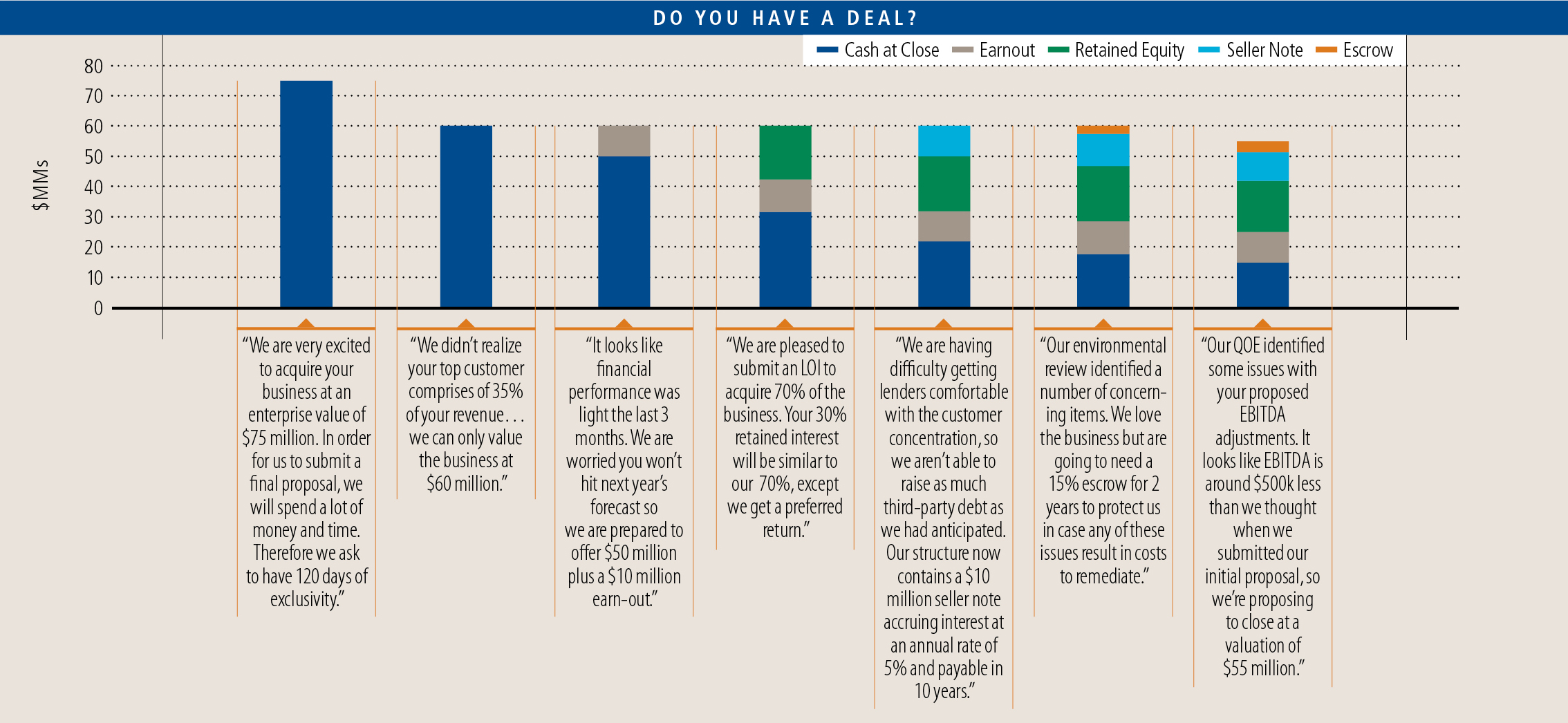

An extreme hypothetical example illustrates how far a deal can stray from the initial proposal. In this example, the seller receives a letter from a private equity firm indicating great enthusiasm for acquiring his business for $75 million. The owner finds this very attractive and can’t wait to spend that money purchasing his own private island. The graphic below shows how the deal morphs (the blue bar represents the reducing amount of cash at closing) over time with initial terms replaced with alternate structures favorable to the buyer.

Wasting no time, the owner signs a brief document agreeing to grant exclusivity to the buyer, which prevents the owner from speaking with any other prospective buyers during this time. Now knowing the owner has no alternatives, the buyer begins its diligence investigation. Sure enough, the buyer was unaware that 35% of the company’s revenue comes from one customer, a risk many private equity firms are unwilling to underwrite (see nearby, “Customer Concentration: there is more to concentration than a revenue pie chart”), or only at a lower valuation. In this case, the proposed purchase price drops to $60 million.

Meanwhile, the owner’s diligent response to the buyer’s information requests weakens focus on the sales team. As a result, revenue dips a bit, causing the buyer’s confidence in the forecast to decline. The buyer addresses their concerns by asking for a $10 million earn-out, reducing the cash at closing to $50 million. However, the big shock comes shortly thereafter, when the buyer presents a more detailed term sheet proposing to acquire 70% of the company’s equity, with a requirement that the owner reinvest 30% of his interest into the newly-capitalized business. Further, the buyer’s investment will be preferred to the seller’s position, which includes a preferred return as well. Cash at closing has now dropped to $35 million and the risk position of the remaining amount has increased.

But wait, there’s more! Trouble raising debt financing, accounting issues during the buyer’s quality of earnings investigation, and concerns identified during the buyer’s phase I environmental review continue to whittle down the deal to what is now unrecognizable from the original $75 million offer. In our hypothetical example, the owner’s bank account receives roughly $18 million at closing, resulting in a significantly smaller private island.

All Deals Have Issues

The example presented here is extreme, but nearly all deals encounter some of these issues. To avoid these late-inning surprises, sellers would be wise to consider a competitive process that provides interested parties all relevant information necessary to put forth more comprehensive proposals. At that point, owners can then have confidence that they are getting a market deal that is far less likely to get “re-traded” prior to closing. However, running competitive processes without expert help is not easy. It is extremely time consuming, which risks distracting a seller’s team from the day-to-day business.

Preparation and competition are the keys to achieving the best result. Keeping the interested party at bay while taking the time to prepare properly is difficult, but has paid off over and over for the patient and disciplined.