Past issues of Insight have commented on the advantages of teaming up with a private equity firm in a leveraged recapitalization. This form of transaction provides liquidity for business owners, while assuring the continuity of the organization and management team. The steady proliferation of private equity capital funds makes it likely that owners and managers will have multiple investors from which to choose. If this is a direction appropriate for your situation, there is a whole range of issues that should be considered in the selection of a capital partner for the business, aside from valuation.

Know whether the private equity group has readily available capital.

Equity or buyout groups come in two varieties; those that have committed pools of capital, and those that have pledges of capital. The key distinction is who makes the investment decision. In the case of a committed pool, the fund managers have the authority to invest capital on behalf of partners. In a pledge fund, the manager offers an investment to the pledge group of investors and they individually make the decision whether or not to invest. Depending on the particular relationship between the manager and its pledge partners, dealing with a middleman may make the transaction far more difficult to complete.

Does the prospective fund fit the anticipated transaction size?

It seems like an obvious question, but there can be a catch. An equity fund will expect that 60% to 80% of the recapitalization transaction will be funded with debt and the remaining 20% to 40% of the capital structure will be equity. Typically, an equity fund will limit its investment in a single transaction to no more than 10% to 15% of its committed capital. So, for a $100MM fund, the maximum investment would be in the range of $10MM-$15MM. Given reasonable financial leverage, that would equate to a total transaction in the range of $30MM-$45MM. Do the math and understand the capital structure before selecting a partner.

Issues To Consider When Selecting a Private Equity Partner

- Know whether the private equity group has readily available capital.

- Does the prospective fund fit the anticipated transaction size?

- Your equity partner should have additional resources to bring to the table.

- Understand an equity partner’s investment horizon.

- Investigate your prospective partner’s capacity to support its investments.

- With whom will the management team and the shareholders be working?

- How does the equity firm react to stress?

- What fees will your partner expect to extract from the business?

Your equity partner should have additional resources to bring to the table.

It is important that the partner you select has the capacity and willingness to invest additional funds in the business when either unexpected opportunities or stumbling blocks present themselves. If your capital partner is out of dry powder at the critical time when additional capital investment is needed, the potentially uncomfortable and costly alternative could be an untimely sale of the business. Moreover, it is wise to have detailed discussions and a clear understanding as a part of the investor selection process about how additional capital would be invested in the business.

Understand an equity partner’s investment horizon.

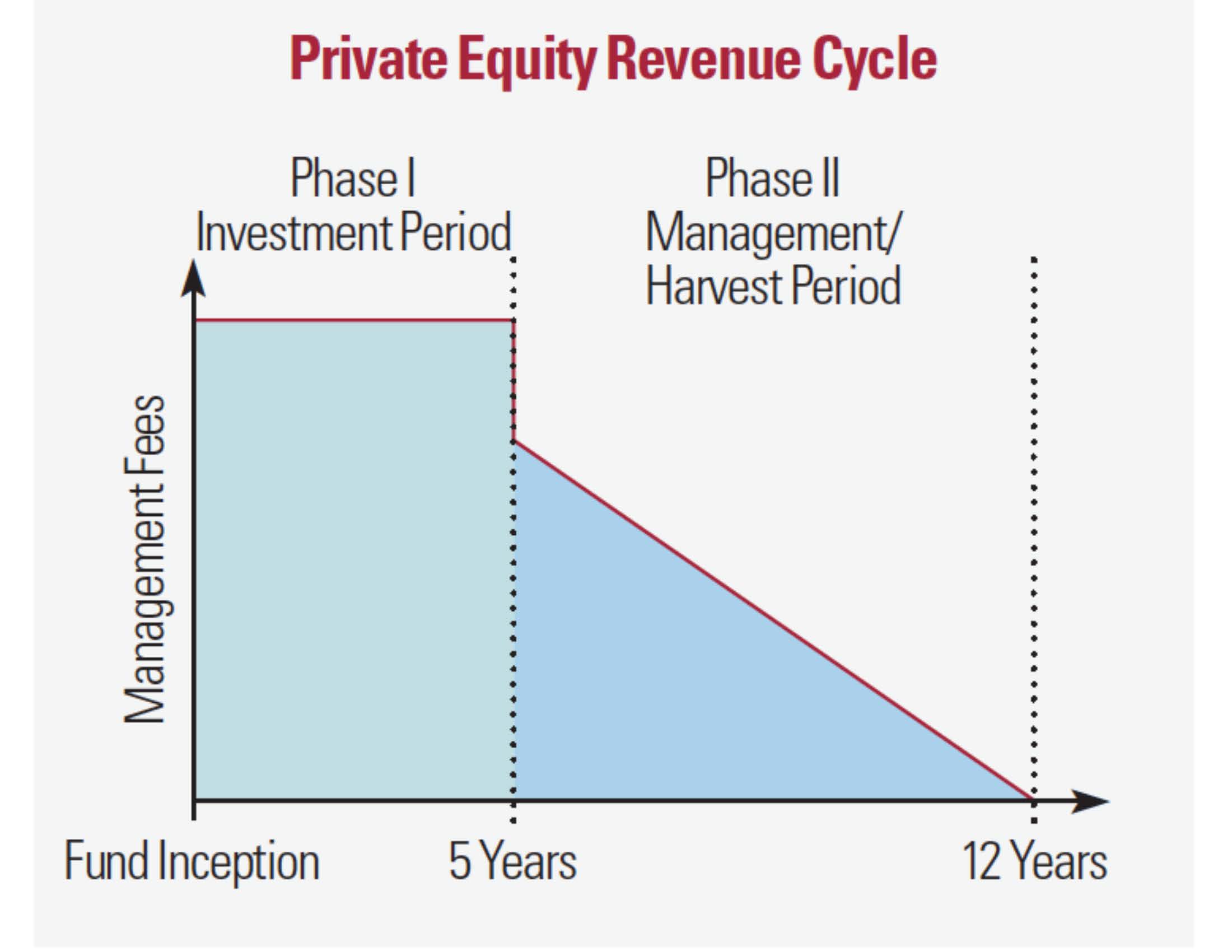

Each equity fund has a finite lifecycle (normally 10 to 12 years) during which funds are invested, investments are nurtured, and ultimately, the value that has been created is harvested. Partnership agreements spell out the time period the fund managers have to invest the money, how they are paid, and when the investments need to be harvested. As the fund moves through its cycle, the investment horizon for individual investments becomes shorter. If there is little or no unused capital remaining at the time your company needs additional investment, do not expect an investment from the managers’ next fund, as they do not like the conflict of having two separate funds invested in the same company at different valuations.

Investigate your prospective partner’s capacity to support its investments.

A fund’s life cycle and investment horizon have a bearing on the staff and resources available to support the investment portfolio. Operating an equity fund is a costly exercise, principally supported by the annual fees earned by the fund manager from the fund and its portfolio investments. A private equity firm with multiple funds under management, and the track record and inclination to raise additional funds, is likely to be able to support the overhead associated with maintaining a stable and experienced team to manage and support its investments.

A fund’s life cycle and investment horizon have a bearing on the staff and resources available to support the investment portfolio. Operating an equity fund is a costly exercise, principally supported by the annual fees earned by the fund manager from the fund and its portfolio investments. A private equity firm with multiple funds under management, and the track record and inclination to raise additional funds, is likely to be able to support the overhead associated with maintaining a stable and experienced team to manage and support its investments.

Consider the fee revenue cycle shown in the chart to the right. In phase I, fund managers typically earn fees as a percentage of total committed capital (whether or not deployed), while they are principally engaged in finding and closing investment opportunities. At some point, as committed capital is substantially deployed (often near the 5-year mark), the emphasis turns to managing and harvesting the stable of investments that has been assembled. As Phase II begins, the management fee is reset, predicated on the actual dollars invested. From that time forward, the fund manager’s revenue stream declines as the investments mature and are harvested. If the fund’s investments are successful, then the manager earns a share of the gain (typically 20%). If a firm is unsuccessful or manages only a single fund, pressure will mount to cut expenses as the revenue stream declines and this could affect the support you expect from the organization and the stability of the people you think of as your partners.

With whom will the management team and the shareholders be working?

As a transaction develops, a number of people from the equity group have roles in underwriting, negotiating and closing the investment, but not all of these folks are likely to be involved on a continuing basis. You need to know well the people that will have a continuing role in the business and will populate the board. Their personal backgrounds, temperaments, and the skills they bring are important considerations. Industry contacts, transaction experience, knowledge of public markets, and organization-development expertise may be beneficial to the effort to maximize the future value of the business. Do not be satisfied with vague allusions to helping direct the corporate strategy. A precise understanding of the expected roles and the skills and experience that support those roles is a reasonable expectation.

How does the equity firm react to stress?

Business is business, which means everything doesn’t always turn out as planned. When a portfolio company hits a significant rut in the road, how do the decision makers at the equity firm react? Do they provide rational support for decisions; are they reasoned and deliberate in assessing accountability; do they draw quick, unsubstantiated conclusions; or do they attempt to micromanage the business, either directly or by turning up the demands for information and financial reporting? It is difficult to predict how human beings will react when the chips are down. The experience of former operating partners offers valuable insight into how a potential capital partner will handle adversity. So, seek out their advice.

What fees will your partner expect to extract from the business?

The economics of your investment can be impacted by significant transaction and management fees charged to the company. This often comes as a surprise to the operating partner, because it is not readily understandable why the equity firm would be charging itself. In most cases, it is the fund managers that benefit from these fee arrangements, rather than the equity fund itself. In essence, the manager is charging additional fees to its fund investors. However, minority shareholders, like you, will be footing part of the bill.

If a company is being sold in its entirety, many of these issues are unimportant; but if an owner plans to bring on a new partner while retaining an interest in the business, it pays to investigate the backgrounds, styles, and incentive systems of the people who may fill that role. The importance of a good philosophical and personality fit between shareholders, management, and the new capital partner cannot be overstated.