The directors of such [joint-stock] companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private co-partnership frequently watch over their own. Like the stewards of a rich man, they are apt to consider attention to small matters as not for their master’s honour, and very easily give themselves a dispensation from having it. Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company. —Adam Smith (1776)

As Adam Smith observed centuries ago, non-owner managers cannot be counted on to naturally make decisions that maximize the value of the firm. More recently, Harvard Business School and University of Rochester professors Michael Jensen and William Meckling observed in a 1976 paper “that managers with limited investment in the firm they have been hired to manage are inherently selfish. They will divert firm resources away from opportunities that create the most firm value and towards those that bring the most value to the individual, such as perks, notoriety and empire-building.”

Acknowledging this phenomenon, many business owners wisely craft incentive plans to reward managers that strive for better performance by aligning their interests with those of equity holders. Although these schemes are designed by well-intentioned business owners and documented by diligent lawyers, we routinely see incentive plans that fail (sometimes miserably) to accomplish that objective.

Aligning Interests

Owners should seek to assure that the value of the equity invested in their business grows at a rate sufficient to justify that investment. Equity value grows in only two ways, 1) either by expanding the value of the entire enterprise, or 2) by paying off debt.

The benefit of paying off debt seems obvious, the quicker the better. Funds to retire debt originate from operating cash flow and from reducing the amount of capital that must be invested (both in working and fixed capital) to operate the business.

Increasing overall enterprise value only occurs if operating cash flow sufficiently compensates for the cost of the capital invested in the business. Business owners overlook this fact in the belief that management should be rewarded simply for growing sales or profits (defined as EBITDA or net income, among others). The allocation of new capital to produce growth is often ignored.

Creating value by generating returns in excess of the cost of capital expands the overall pie. In contrast, reducing debt (all else equal) simply reallocates the slices of the pie (increasing the equity slice at the expense of the debt slice). In either case, providing incentives to managers to consider business decisions based on this framework results in an alignment of interests.

Unintended Consequences

We recently reviewed an incentive plan that rewarded management for exceeding certain EBITDA targets. Based on the owner’s goal of selling the business in five years, the plan was designed to pay an incremental bonus calculated as a proportion of the increase in EBITDA over a certain timeframe. The problem was that no consideration was made for the amount of capital that would be invested to achieve the desired goal. A couple of years into the plan, EBITDA was indeed growing but at a proportionately slower rate than the amount of capital invested to support that growth. The result was a plan that rewarded the manager at the expense of the owner.

In another notable example, our client rewarded managers for achieving a performance target with a cap. The owners found that performance rarely, if ever, exceeded the bonus pool cap, but when performance dipped below the bonus range, profitability dropped off considerably. Management appeared to be gaming the system. When performance was expected to exceed the annual cap, managers deferred incremental profit to the next period (since there would be no current upside now and the action might also contribute to a downward adjustment to the target in the succeeding period). Conversely, when performance fell below the bonus level, an incentive was created to report even lower performance. Predictably, management understood that subpar performance was often rewarded with a lower bonus threshold in the next period.

Each of these plans unintentionally misaligned management’s actions with the owner’s objectives. Perhaps just as destructive, over time we observed that management began to develop a short term operating mentality focused on cost control rather than opportunity development and seemed to lose discipline over working capital investment and fixed capital spending. Not a winning long-term strategy.

Some businesses attempt to solve the misalignment problem by granting equity (or options) to management and/or imposing financial discipline by loading up on debt. Certainly, this is the model pursued by many private equity investors. However, providing equity has its own unintended consequences and, as argued by G. Bennett Stewart, “stock and stock options are like issuing only one report card for a whole class of students.”

An Alternative – EVA Bonus Plan

Economic Value Added (“EVA”)1 measures the growth in the value of an enterprise by reference to the costs of the capital invested in it. In addition to measuring value, EVA, when incorporated into management incentive plans, replicates features of equity-based compensation (unlimited up and downside incentives, objective external targets, high correlation with shareholder value, minimized accounting distortions, etc.) while providing clarity of measure.

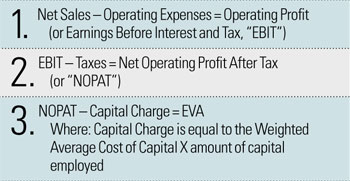

EVA simply subtracts a charge for the cost of the capital employed from the after-tax operating profit. Specifically:

Align Incentives with Value Creation

EVA encourages managers to make decisions that consider both operating and capital costs to determine how business choices might impact shareholder value.

Like shares of stock, EVA measures the value of the company as a whole.

However, unlike stock, EVA bonus pools can be pushed down many layers into an organization to measure the performance of a division, a factory, a store, a product or a customer—wherever one can reasonably allocate revenues, operating costs, and capital investment.

Furthermore, when given EVA targets, managers (who have an incisive understanding of the business) gain the flexibility to choose which levers to pull—revenue, operating cost or capital investment—to maximize their relative contribution to firm value.