The Market

Our reference to market means the market of buyers and investors that provide liquidity to owners of privately-held middle market size businesses. That market has changed dramatically in the last thirty years. For reference, prior to 1980, most privately-held businesses were bought either by other companies, when there was a strategic reason for that combination, or were bought by managers, usually financed by the seller. The rationale for a ” liquidity discount” had real meaning because very few businesses had a ready liquid market. The emergence of the private equity industry was a response to that perceived need and by the early 1990s was still in its first decade.

Strategic acquisitions occur when companies believe they can acquire through an acquisition of another business market share, capacity, resources (both human and real), or technology/knowhow that will aid the buyer in its future competitiveness. The motivations for private equity, on the other hand, were originally more of a financial engineering exercise where a business was bought for a low enough price and could be leveraged with cheap enough debt so that after the business repaid the debt and the company was sold, the equity investors would return a profit. The credit markets’ willingness to provide debt was a limiting factor and therefore constrained private equity to businesses with adequate collateral and steady reliable cash flow streams.

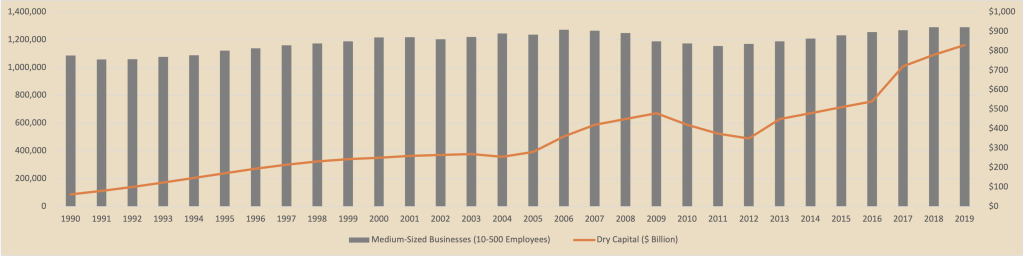

The private equity industry grew to fill the gap as a generation of owners of businesses created after World War II sought liquidity. But, Exhibit 1 shows, the relationship of available capital (measured by uncommitted private equity capital) relative to the number of middle market businesses was quite different than it is today. The difference is even greater than shown as the amount of today’s available capital is understated because it doesn’t capture the informal private equity world of family offices, direct investments, and investors supporting independent sponsors (What to Expect from Independent Sponsors, Spring 2020 Insight).

Exhibit 1: Available Dry Powder Capital Relative to Number of Middle Market Businesses

Over time, the credit markets evolved such that the limitations of commercial banks, which through regulation required low leverage and adequate collateral, were supplemented with unregulated capital pools such as cash flow senior debt, mezzanine, second lien debt, and unitranche capital. In 1990, these sources did not exist in any meaningful amount, whereas today, a great portion of private equity buyouts are funded by non-bank credit sources. These capital sources, teamed with private equity, provided a tremendous surge in available capital to fund acquisitions.

Thirty years ago, capital for the purchase of private middle market businesses was in short supply; today, it is business opportunities that are the constraint. Competition among private equity investors in the early stages of the industry was limited and equity firms drove hard bargains on prices with the objective of delivering a high rate of return to their investors. Although not always achieved, if the private equity firm couldn’t see a clear path to a 30+% IRR on its equity investment, it would just keep looking. These returns caused money to pour into the private equity industry as it represented such a premium over the long-term public equity return of 7.5%. Today, an expected return of 15% looks very attractive and still attracts more capital to these investments. Competition among buyers drove returns down and prices up for privately-held businesses and made private equity competitive in certain cases with strategic corporate buyers. Exhibit 2 shows the progression of EBITDA multiples (the price of the business relative to the amount of EBITDA generated) over time.

Exhibit 2: Change in Average Price of Private Businesses (EV/EBITDA)

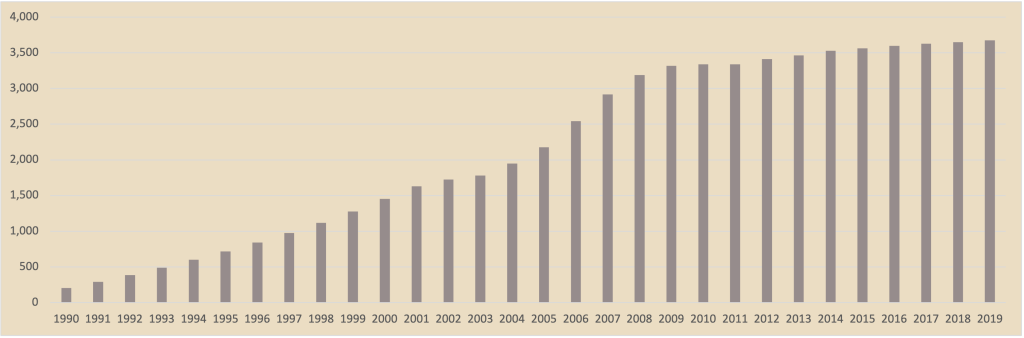

As the industry evolved, firms carved out competitive niches by industry, size, stage of evolution, and type of investment (e.g., full buyout, majority investment, minority investment, preferred equity) which, with the accommodating credit markets, allowed virtually every type of business to have access to private equity. Exhibit 3 shows the growth of the number of firms over time.

Exhibit 3: Number of Active Private Equity Firms Over Time

The 1990s version of private equity relied on a low purchase price, very steady and reliable cash flows, and available cheap debt. The 2020s market of private equity is largely industry agnostic and is not reliant on a formulaic capital structure. The industry has evolved from searching for a specific type of business that would fit the leveraged buyout formula to searching for return with the type of investment customized to fit the situation. In essence, private equity has morphed from trying to fit businesses into its fixed set of boxes to applying capital in whatever way makes business sense.

The effect of all these changes has been that private equity firms have become much more flexible and competitive. In the 1990s, an offer from a private equity firm would be meaningfully lower than from a strategic business, take much longer to close, and have far more contingencies to closing a transaction. Today, private equity firms can often go toe-to-toe with a strategic buyer and win the transaction in price, timing, and certainty of a deal.

The bottom line is that today’s market for monetizing the equity in a business is far more liquid than thirty years ago. Available capital, competition, and knowledge have created a competitive market for a seller of a business. With there being more capital than investment opportunities, it is and will be a seller’s market far into the future.

Tools and Information

It is hard to fathom from the perspective of today how different the availability of information was just thirty years ago. Knowledge was proprietary and, in that environment, large investment banks had a distinct advantage. Research was expensive and could only be justified when spread over a large base. Whereas a banker in a national firm could have access to its own proprietary research staff, expensive databases, and proprietary banks of institutional knowledge, an aspiring middle market banker could tackle the same task by contacting industry organizations, potentially buying expensive economic research reports, conducting library research, or talking to people in the industry.

The information age changed all of that and has had several major positive impacts on the industry of monetizing private business equity:

- The playing field has been leveled to allow big and small firms to offer competitive advice.

- Access to information has reduced the cost of acquiring a suitor/acquisition target by making more knowledge available sooner thereby reducing the amount of “frog kissing.”

- The speed of information exchange and tools for sharing information has reduced the time and cost friction of completing a transaction.

Wherein the differences between big and small advisory firms used to be stark, pretty much everyone now uses the same tools and accesses the same information resources. An individual analyst, regardless of who owns the desk, can produce high quality research and presentation materials from a desktop. An advisor’s experience and knowledge is not limited by the number of employees in the firm.

Technology has allowed access to information that allows sellers to have more confidence that a transaction is done with “market” knowledge. In the 1990s, a target buyer list might have been a dozen or two dozen names; today the number is in the hundreds. Conversely, a buyer might have had little knowledge about a potential acquisition before engaging in a sale process. A lot of frogs needed to be kissed to find the prince. Today, buyers can have a lot of confidence that it knows about the company’s business, its people, and its markets before serious engagement, while the seller can assure itself about the buyer’s profile and reputation. All in all, these technology improvements have increased the probability that any buyer expressing interest is actually interested.

These tools have increased the productivity of everyone in the deal value chain. Electronic data room sites routinely are used to share due diligence materials. This can be compared to what was literally a “data room”, where buyers would need to travel to plow through physical documents. Legal documents used to be drafted by “typing pools” interpreting lawyers’ handwritten scribbles. Closings used to be a physical event where everyone on the two teams showed up to a law office conference room where multiple copies of each document were physically signed. Today, all documents and signatures (some electronic) have already been exchanged before the closing, with the only remnant of a closing being a telephone call with both sides’ attorneys confirming they have what they need, and a closing is declared.

The ease of document exchange has led to great improvements in productivity but the human reaction to these changes still leaves some room for further improvement. One example is in the manner in which deal lawyers work with each other. Dealmakers today are all familiar with the multiple-draft vortex that produces document changes but not resolution. Attorneys may never physically meet with opposing counsel and, sometimes, not even with their own clients. Losing the tension of a face-to-face confrontation allows advisors to hide behind the keyboard and avoid “hearing” the opposing party. The skilled negotiator of yesteryear has been replaced with a back and forth of articulate, clear and convincing arguments for a position. What used to occur in real time now can take longer because each exchange can be thought about in uninterrupted silence until a formulation is ready.

The COVID pandemic may have contributed to even more commoditization of the deal. We participated in several sales closings without any of the parties (including principals) physically meeting. That was unfathomable before the pandemic. Remote work has become a mainstay for many of the professionals in the deal process. Whereas attorneys on opposite sides of a deal may never meet, lawyers within their own firms may not now meet.

Setting aside any considerations of the impact on cultures and organizations, the ability to exchange information across many media types has reduced the cost and time friction of getting deals done, contributing to the increased liquidity of the market.

The Practice of Investment Banking

Middle market investment banking has radically changed over the last thirty years as the industry has evolved along with the overall market. To contrast the two ends of the time spectrum, a successful investment banker in the 1990s was first and foremost a great business analyst and transaction negotiator, whereas the successful investment banker today is primarily a market expert and process manager.

A typical middle market client in the 1990s was entrepreneur-founded and managed. The CEO (and probably the owner) was the decision maker on most all major economic events. That person had negotiated many significant (to the company) business transactions, was confident in the business model which was largely based on experience and had a value perspective limited to the public stock market and metrics related to a friend’s deal (x time sales, or y times widgets). That owner was also the primary competition to an investment banker.

Rather than investment banks competing against each other, the more common value proposition challenge was whether the banker could add any value in a negotiation relative to what the owner could accomplish. Since the private equity market was still in its infancy and represented a poor second choice relative to a strategic transaction, the relevant question was whether the banker could achieve a better outcome than could the owner. In that environment, a premium was put on understanding value from the buyer’s perspective by being a great business and financial analyst that could portray the business in a manner that revealed the value to the buyer and the ability to negotiate a deal that reflected the value to the buyer.

A successful investment banker in those days needed to understand the detailed fundamentals of the business and portray it in financial terms. In today’s parlance, the investment banker was often also the QOE analyst. The same banker was somewhat a renaissance transaction specialist. Using the television commercial phrasing, “ I may not be a tax, legal, or accounting expert, but I stayed in a Holiday Inn Express,” the banker was knowledgeable about all those topics and was also most often the lead negotiator on all terms of the deal, reviewed all legal documents (sometimes before they were sent out), participated in all due diligence, created schedules, and was the quarterback to all deal related activities. The role selected for analytically skilled bankers who had a keen grasp of intrinsic business value and strategy. Investment bankers looked very much like their counterparts in big corporation corporate development and private equity because the deal was dependent upon being able to communicate in the language the buyer used. Understanding the buyer’s decision-making processes and the way they determined value was critical to negotiating a deal that reflected the value being acquired. As a result of that thinking process, bankers often weighed in on the question of “should a deal be done”, not just what could be done.

As the private equity market grew in size and importance, investment banks gained another set of skills and knowledge that was distinct from any owner’s knowledge – the knowledge of the market. At first it was “who”, but later developed into a much greater and nuanced knowledge of individual firms, their reputation, how they acted in deals and after closing of deals. This was valuable to sellers. The first middle market firm to recognize this trend in private equity and capitalize on it was a firm out of North Carolina named Bowles Hollowell Conner. It targeted private equity firms both as a market and as a client. The emphasis on that market allowed it to develop its own proprietary database on many private equity firms that gave them credibility with clients. They found beneficial feedback as the better they competed for seller clients, the more private equity firms became dependent on BHC for deal flow. The reward was assignments to sell portfolio companies of these same firms. After the firm was bought by First Union Bank (later to be part of Wachovia) in 1998, two partners, Christopher Williams and Hiter Harris, formed Harris Williams, which perfected that model to an even higher level.

Recognizing that private equity firms were somewhat homogenous and that they had everchanging investment priorities, successful investment banks realized that having a broad exposure of their clients to this market was beneficial and the practice was copied throughout the industry. Banking organizations evolved to emphasize market access. The theory was that if there was enough competition, one-off negotiations and problem solving were less important skills. In the meantime, accounting firms rushed into the fray to offer the business analyst skills that bankers used to provide. Specialization is a natural development in a growing market and that is what happened to bankers. To efficiently deliver the market, repeatable systems were developed such that each seller could be efficiently exposed to many (sometimes hundreds) of buyers. Successful bankers don’t have to be the best business analysts, but they do have to know how to manage a process. That may not sound like much but keeping track of several hundred different buyers, negotiating non-disclosure agreements, answering questions, and managing due diligence processes, while helping the client through this process takes logistical skills and plenty of coordination. Banks developed assembly line type repeatable processes and hired people to man the positions, pushing as much throughput as possible. As the job changed, so did the people. As banks became more market and process focused, the overlap of the skills and people with private equity firms diverged. The overlap was not as critical as the skilled art of persuasion was replaced by the competitive bid. Less concerning was the judgement of how good the deal was on an intrinsic basis, rather emphasizing the market reality.

Investment banks will continue to evolve, mostly along market lines. Industries are often touted but there could be other segmentations of the market that become valuable. Specialization will continue with bankers reflecting the changing shape of the markets with the ultimate objective of knowing the parties comprising the market and knowing their declared interests and investment preferences. This knowledge will continue to be delivered as a service to allow efficient access to liquidity.

Zachary Scott

Relying on corralling and managing a competitive market to deliver the best result can be effective in many situations, but not all. Some businesses have value that is not immediately apparent from the financial statements and may require a deep fundamental analysis of the market position and the strategic importance of the business. The case may need to be made in a persuasive manner through direct negotiation. This type of approach and capability is most critical to achieving sales of complex businesses, particularly in strategic combinations, an acquisition, where its success or failure will not be known for years following the deal, a merger of industry competitors, or in a restructuring of a business in distress. Zachary Scott’s mission is to help business owners extract and realize value from their businesses and investments where our background in how to understand the intricacies of the business and market dynamics make a difference in the outcome. Our job is to find the path less traveled when it leads to a better destination.